Kashmir: the problem & the solution

The renewed struggle by Kashmiris against occupation by India has left no ambiguity over the issue of Kashmir. The facts are crystal clear. Every one knows that there is a dispute over Kashmir between India and Pakistan, that the UN Security Council passed a resolution in 1949 outlining a solution by a ‘plebiscite’ that was accepted by India as well as Pakistan. Under the Resolution, both countries agreed to: 1) cease fire, 2) and hold a plebiscite to allow the people of Jammu and Kashmir to decide which country – India or Pakistan – they wanted to join. The fighting by the two armies did cease but the nightmare for the people began. They could not go across the cease-fire line; they could not meet their relatives or go to the Punjab and the Frontier Province of Pakistan as they had done for a hundred years to escape the harsh winters and in search of livelihood.

The Muslims of Kashmir had family ties with Kashmiris in Pakistan and their trade was also mostly with Pakistan. Both were disrupted. The Kashmiris thought that the disruption would be temporary; after all India and Pakistan had both endorsed the UN plan for plebiscite. Months of waiting prolonged into years and then decades but there were no plebiscite – just excuses and delays. Pakistan had a duty to liberate Kashmir because Kashmir being a predominantly Muslim state. It did try in 1965 but India decided to expand the war beyond the confines of Kashmir. But neither country could sustain an all out war very long and the UN intervened to arrange another cease-fire. The stalemate that resulted was favourable to Pakistan but its erstwhile ally – the United States – had abandoned it. The Soviet Union – the friend and ally of India – mediated a settlement called the Tashkent Declaration. It did not deal with the question of self-determination and merely restored the Cease-Fire Line supervised by the UN observers. The leader of Pakistan at the time – General Ayub Khan – became very unpopular because the people expected him to win a decisive victory in Kashmir. He was neither able to secure victory nor to use the edge Pakistan had to secure self-determination in Kashmir. He was forced to resign in consequence of extensive demonstration against his rule.

The next war in 1971 was started by India. Its objective was the secession of East Pakistan. America as well as the Soviet Union supported the invasion and the Indian objective of secession of East Pakistan. The war was lost with 93,000 prisoners of war in Indian hands. The people of Kashmir had hoped that Pakistan would launch an attack in Kashmir to make a countervailing gain. They were shocked when it did not. It was true that East Pakistan – separated by a 1000 miles of Indian territory from West Pakistan was difficult to defend but the incompetence with which diplomacy as well as war were handled was a huge disappointment. It is pointless saying whether it was the ineptitude of Pakistani leadership or the imbalance of power that had made a military solution of Kashmir so difficult, but the decisive defeat of Pakistan in 1971 War and the forced separation of East Pakistan to make it Bangladesh did have an impact, albeit temporary, on the confidence of Kashmiris in Pakistan’s capability and political will.

The tide did turn in favour of the Muslims in general and Pakistan in particular towards the end of the decade. The Muslims did successfully resist Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

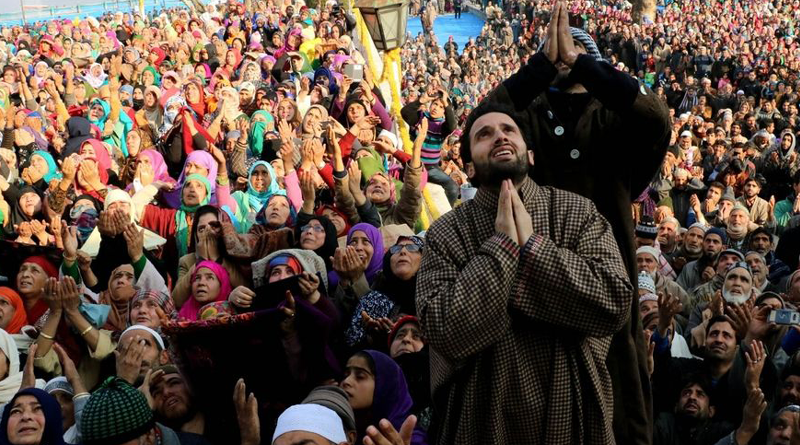

Now a struggle has started in 1989 and has continued ever since. What is the basic message that emanates from the Kashmir situation? What is the fundamental truth underlying the fifteen years of tumult and insurrection? Do the people love coming into streets, braving the bullets, killing and getting killed? Is there nothing to life other or more than that? Life is the dearest thing that any one possesses; family often the next on the list. Just living is worthwhile and of value disregarding the high-minded compulsions of community or national life. Why should the people of Kashmir take the route that put their lives at risk and forsake life’s pleasures? Thousands (perhaps close 100,000) of them have been killed, countless women dishonoured, houses burnt, people displaced, businesses shattered, why after all should this happen? What makes a people, so to speak, opt for it – choose a course where this is bound to happen? There is an answer to it. It is short answer but one that sums up the crux of the matter. That single sentence answer is: the Kashmiri people have never accepted India’s sovereignty over Kashmir and they want to put an end to Indian rule over them.

One may ask: how come then that India has been ruling Kashmir through a democratic setup? The answer is that the whole set-up is a farce – a total sham. Democratic institutions are only a smoke screen; the real power is in the hands of the Indian intelligence and the military forces. The Chief Minister, his Cabinet, the State Assembly – all are the props of a puppet show. India cannot rule Kashmir if the state operated under the rule of law and true democratic dispensation. India rules by complete disregard to the rule of law. Any one can be picked up from his house, or from work or enroute from one place to another and disappear.

Taking the life or honour of a Kashmiri is not a crime; it is legitimate action in crushing the rebellion. India does not care if its rule is considered occupation. For the Indian soldier it is a matter of pride to have the life of a people in their hand – to kill any one he like whenever he likes with impunity.

Kashmiri struggle has entered a crucial phase with the initiation of a dialogue process between India and Pakistan. Viewed in its overall context, the joint declaration by President Musharraf and Prime Minister Vajpayee made on the eve of SAARC summit in Islamabad that kick started the dialogue process may turn out to be historic or it could be another damp squib. It is too early to make any prediction but it is wise not to discard it as ‘tactical’ move by India even though that is what it might turn out to be. However, the talk of ‘give and take’, compromises and flexibility’ worry the people of Kashmir. It is a cause of anxiety and apprehension that India and Pakistan may treat the Kashmir dispute as a land dispute. No, it is a matter of principle. It deals with hopes and aspirations of a people; their dignity and honour; their life and liberty; their conscience and convictions.

It is often said that India and Pakistan, once they enter into a dialogue, should show flexibility. That is quite natural; a dialogue cannot proceed without some sort of flexibility. However, it is not clear what this would mean when it comes to resolving their dispute over Kashmir. If the issue was Siachin, an uninhabited glacier, one could understand what would be the implication of ‘flexibility’ in resolving the issue. When the third element in the dispute is an inanimate entity that does not have its own aspirations or agenda, flexibility or ‘give and take’ have territorial connotation. Kashmir, obviously, is different. Here it is a question of a people who have to determine their political destiny. In the dialogue process between India and Pakistan, Kashmir occupies an autonomous position – a position that is independent of what India and Pakistan say; it too has something to say. A dialogue on Kashmir must reflect this right from the start. The dominant theme in the political discourse surrounding the dialogue process should be the finding out of the real aspirations of Kashmiri people, and it is with that clearly spelt-out that India and Pakistan should start the process of resolving the problem.

The negotiations would come to nothing if India and Pakistan start linking huge stakes with their respective views. In that event they would seek a ‘favourable solution’ and associate success with their point of view prevailing. If that happened, the dialogue would be unproductive, even counter-productive. For example, if India approached the dialogue process by making loud noises (as it has been doing to its domestic as well as in foreign audiences) that India will break up if Kashmir cedes, and that Kashmir is the cornerstone of its secular fabric, the result of the dialogue would be increased bitterness – a political breakdown not a break through. This approach has brought the objectives of India under suspicion from the people of Pakistan as well as of Kashmir. Against the backdrop of such objectives, the interlocutors of India would be condemned as traitors – ready for a ‘sell out’. It would destabilise Pakistan even further and perhaps lead to change in its leadership. It appears that the representatives of Kashmiris would not be invited to participate in the parleys at the outset. There would be little fall out on them but they would certainly become even more distant from Pakistan and rely on themselves and invite support from farther afar. Kashmiris could internationalise their struggle in manners as yet not contemplated. The bloodletting in Kashmir may reach scales unprecedented and yet unexpected.

The fact is that the Indian stance has no basis. India does not have a principle of national solidarity that defines it as a ‘nation’. The caste system that the Constitution bans but the people suffer in salience denies dignity to a majority of people in India. Its structure of internal oppression prevents the crystallisation of a wholesome political personality and a national identity. By insisting that India rule over Muslim majority Kashmir underlines its secular identity, it actually withdraws recognition to Pakistan where the Muslim majority did secure national self-determination. While India says it wants to de-link Pakistan and Kashmir, its argument reinforces the link. India ridicules Pakistan and justifies its ruthless crushing of Kashmiri struggle for self-determination insisting that both are undeserving of sovereignty because their national identity is a ‘religious identity’. Pakistan is indeed the product of the Muslims exercising their right of self-determination, what is India the product of? Imperial succession? Which Empire? The British Empire? How? Why? By asserting its right to have political control over all of the erstwhile British Empire in India, it de-legitimises itself. Imperial succession, is the not a validation of the polity of a country. If India does not recognise that the creation of Pakistan by the Muslims exercising their right of selfdetermination avoided a civil war in South Asia, it puts its imperial designs on display and courts the threat of a perpetual war that it avoided in 1947.

If India continues to harbour imperial intentions, it would suffer the same fate as all the other empires; it would disintegrate. War and repression are not tolerable in any part of the world as viable instruments for establishing or expanding empires; reliance on coercion provides basis for perpetual strife. India has been fighting insurrection in seventeen different areas in its vast empire. All of these are not for national self-determination; some of these are against the apartheid and oppression. It is only by conceding national self-determination that it would deal with its social atrophy and obtain some semblance of national cohesion. India has to restructure itself on the basis of national self-determination if it is to avoid a political collapse. India has to seek friendly relations with its neighbours if it is avoid becoming a tool in the hands of richer imperialists that have designs on different parts of Asia. The people of India need and deserve peace as much as India’s neighbours. By suppressing the movement for self-determination in Kashmir with wanton use of force, it denies itself any prospect of peace within or with Pakistan. Continued hiatus over Kashmir would be the death of India. By going back on its promise to hold a plebiscite it does not only defy international law, it defines itself as an ‘outlaw’ state that denies the universal principle of ‘national selfdetermination’. It is by such defiance that India has made itself an international pariah and a regional scourge.

India is quite wrong in its assertion that its rule over Muslim majority Kashmir underlines its secularism. It proves the exact opposite because India rules it by force not by consent. But a secular identity is important for India; it cannot be anything other than a secular country because the Hindu religion that sanctions and perpetuates divisions and apartheid of the caste system cannot provide the basis for national solidarity. That it rules Muslim majority Kashmir by powerful military presence and resort to repression even genocide proves that India’s secularism is a farce; that it is an imperial state kept together by force and coercion. It has brought under the microscope other inequities and injustices that India has been able to sweep under the carpet.

The threat of the ‘break up’ of India(in case of Kashmir’s cession) is scare mongering that works well with the outside world The prospect of dreadful instability and perpetual conflict in a country of billion plus is scary. But India should look for more sensible ways for underpinning what it calls its ‘secular-composite fabric’. Use of brute force to suppress Kashmiri freedom movement does not prove India is secular; it proves that India is cruel and lawless.

Similarly, Pakistan also should not consider Kashmir’s accession as validation and proof of its foundational principle – the Two Nation theory. The theory, which is doctrinally well founded and practically so well proven, does not need a proof. Islam continued to be the organizing principle of the state right from the time the Muslims established the first state under the leadership of the Prophet Mohammed (SAAW) in Medina in the 7th century. That continued without challenge until as late as the dismemberment of Ottoman caliphate in the 20th Century. Pakistan (with the many languages that its people speak) did not invent a new principle of solidarity as the foundation of a state. Its emergence is the manifestation of the same facts and truths on which Kashmir’s accession with it now hinges.

The principle was already there, in theory as well as practice. Pakistan followed it faithfully and built its national solidarity upon it. If the Kashmiri people follow the same principle, they would also benefit. Whether they do or not, it would not weaken the principle or this particular embodiment of it that exists in the shape of Pakistan. It would seriously hurt the vital interests of the Kashmiri people, and they might come to understand later that having come out one darkness they have landed into yet another. After all, the separation of East Pakistan did not have a snow-balling effect on the rest of the country: Pakistan did not disintegrate further despite the assistance the foreign enemies of Pakistan give to ethnic and nationalistic forces in various provinces. The enemies of Pakistan have not given up but they have been repeatedly frustrated. If the elections to the National Assembly of the 2002 are taken to be an indication, the ethnic forces did not increase phenomenally. On the contrary, these forces are on a sharp decline.

Diplomacy is not an art in which Pakistan excels. Its people are alert and its leaders often the exact opposite. For any dialogue to lead to peace and justice for all, the aspirations of the people, the universal principles and rights of peoples must be centre stage. Sometimes, when politicians are politicking, it appears they are unaware or unmindful of the aspirations of the people of Kashmir. Despite being self-evident, it is necessary to reiterate, for the benefit of India and Pakistan, that the people of Kashmir feel a deep sense of historically built-up deprivation. Kashmir has witnessed long spells of tyrannical rule, the latest being the Dogra rule that lasted until 1947. The vile nature of that rule is thoroughly documented and it is unnecessary to recount its gory details. Suffice to say that the Muslims of Kashmir suffered greatly under these tyrannical regimes. As the colonial empires started to wither away, the subjugated people everywhere began to dream of a future of freedom in a post-colonial dispensation. Kashmir was no exception.

The earliest political formations, that started taking shape in Kashmir in the late nineteen twenties, had clear political agendas. There were movements everywhere, the people under British India were organizing themselves and debating their post-colonial future. Muslim imagination had got a boost with the idea of Pakistan. Democratic choices were being made: the overwhelming majority of Indian Muslims formally voted for Pakistan. Special referendums were held to ascertain the wishes of the people of Sylhet (to join East Pakistan) and in the North West Frontier Province that too voted for Pakistan. After the long night of deprivation and suffering the Kashmiris were also eagerly looking for a dawn of democratic choice. The Dogra monarchy had got to end anyway, Kashmiris were hoping to choose a future. But unfortunately things did not move that way. If they had, there would have been no need for these words of anguish. The Kashmiris expected tears but of joy. What they got were tears shed and dried, shed and dried, again and again until life was no different to death; the distinction between hope and despondency disappeared.

The Dogra rule ended, but what replaced it was once again another tyrannical rule. The dream of a free and conscious choice eluded once again. The historically built-up sense of deprivation deepened even further. The Kashmiri people have been denied, by sheer fraud and force, the opportunity to freely choose their political future. In practical terms, that is the reality and the substance of the Kashmir issue. Allow the people to determine their political future, the issue would be resolved. This is what the United Nations Security Council Resolutions say. That is the solution. That is the only way forward: to allow Kashmiris express themselves. It is vital that the most oppressed and deprived of the world should also experience the ecstasy of direct choice – casting their vote in a free and fair referendum. It would indeed be cruel to deny the Kashmiri people direct vote, their wish must be ascertained directly.[1]

The Problem

After a review of the current situation, it is important to return to the backdrop that defines the Kashmiri struggle for freedom in the context of history and gives it meaning and import. What, in essence, is the problem in Kashmir? The Kashmiris are a Muslim people. They are often poor but very proud. They are one of the most deprived people and still they retain their pride. They are certainly the most oppressed of South Asia and yet they are proud of their Kashmiri heritage. No people in South Asia have suffered tyrannical foreign rule longer than the people of Kashmir and yet they stay unbowed, proud, and robust in defence of their entity. They retain their optimism and their cheerfulness under the direst conditions. It is perhaps because they inhabit one of the most beautiful landscapes on earth; the horrors of oppressive misrule notwithstanding, they are grateful to the Creator for the bounties they are blessed with. Among the bounties they are grateful for, the most important one is their faith – Islam.

Islamic doctrine being creative of a social order and, therefore, of a civilization and a polity, this faith attaches great importance to the defence of physical assets and regards them as absolutely indispensable. The faith of Islam attaches value to its people, their material resources, their lands and territories, their heritage and history. Kashmir being a Muslim land, it constitutes an important physical asset of Islam. Reclaiming the lost assets of Islam is a common duty for every Muslim man and woman, regardless of his/her colour, race or place of birth.

The Kashmir problem, that has remained unresolved for more than half a century – since 1949 – has given rise to a number of peripheral problems. The question of violation of ‘human rights’ is one example, which has cropped up during the last fifteen years of the freedom struggle. It is a real and genuine problem but a shift of focus would make Kashmir appear an exclusively a human rights problem. The result would be that the real problem – denial of freedom to Kashmiris to choose their destiny – would continue to be ignored particularly on international forums. The strategy of ‘buying time’ – postponing the settlement of the main problem by showing readiness to be flexible on peripheral problems – is a good strategy for India but not for Pakistan and Kashmiris. ‘Buying time’ has been the main plank of the India strategy. It makes deals and signs agreements parts of which (that it likes) it implements and the parts it does not like, it makes the subject of interpretation, dispute or controversy. With so much experience of dealing with India, it is amazing how often the Muslim leaders of Pakistan and the Kashmiris have lost sight of the basic problem and start dealing with obfuscations of India on mere promise of parleys.

Basic problems arise or become intractable in consequence of wrong or bad decisions. Because of bad faith, personal prejudice, inducement or falling into a trap, decisions are made that are fraught with evil consequences. The ill effects begin to unfold soon after the decision. It is wise to rectify errors early; the more time an evil decision gets to root, the more its consequences become hard to reverse. In the 1930s, Hindu leaders created proxy elements in Kashmir, who in the name of Kashmiri nationalism opposed the project of Pakistan. They aligned themselves with the Brahmin leaders of the Congress Party and paved the way for India’s armed invasion of Kashmir on October 27, 1947. This was a huge blunder the destructive consequences of which the people of Kashmir are still suffering. If the Kashmiri people had risen early and decisively, it would have been less difficult to undo the blunder. There is a lesson to be learnt from that blunder. It is better to have no deal instead of a bad deal. Sheikh Abdullah had been in the forefront of struggle against the vile rule of the Maharaja of Kashmir. He enjoyed the trust and confidence of the people of Kashmir because of his fiery speeches and bold actions. They failed to take notice that he was on the side of Hindu leaders of the Congress Party not on the side of the leaders of the biggest Muslim Party – the Muslim League. Secular nationalism was a phrase that served as a cover for a trap. As it turned out, the Congress leaders did not honour any of their promises – to Sikhs, to Untouchables or to Kashmiris. The people did notice the arrival of Indian troops but they were not ready to decry the judgment and decision of Sheikh Abdullah. In general ways, they regarded India as an aggressor and movements for Kashmir’s liberation from India, underground as well as open, always existed. However, India did manage to govern Kashmir through its proxy elements – Muslim in faith but ready to overlook the genocide, rape of women and routine use of torture to suppress the Muslim resistance. The Muslim Fifth Column is as much responsible for the genocide; repression and agony the Kashmiri suffer as the Indian armed forces. They provide the fig leaf with which India paints a picture to the outside world of the insurrection being sporadic, foreign inspired and unpopular.

With the emergence of the powerful movement of armed insurrection in 1989, things have changed. There is now an open rebellion in Kashmir against India’s occupation. It seems that at long last a serious resistance movement has got underway to undo the earlier wrongs, and reverse the tide of India’s ever-increasing and comprehensive control over the land and the people of Kashmir. However, much caution is needed. Under no circumstances should the objective of ‘rejecting Indian sovereignty’, which is the basic issue, should be lost sight of. India is an occupying power; it must be dealt with as such. Even at this stage, despite the fact that thousands have been killed, there are many in Pakistan and among the Kashmiris willing to consider solutions that leave the basic issue unresolved. Anything short of ending Indian rule would not solve the problem. It would not end the insurrection, or reduce casualties or ameliorate conditions. It would only prolong the agony of the people and actually defer the solution. India would buy time but time is not on its side. Buying time is neither a wise nor a valid objective for India. Delay favours nobody; these do not save lives or reduce costs. On the contrary, submission to delaying tactics accumulate losses and keep a hope alive in India that it might make gains, even keep the part it occupies, if only it was harsher in its repression and persisted longer in its occupation.

The logic of ‘good’ is simple: a right step has inherent good in it, which shows up and multiplies over a period of historical time through generations. Likewise, a wrong step has nothing in it but evil. Its evil consequences accumulate with each passing moment forming huge obstacles on the path to remedy – the path through which one would seek to undo the wrong. The earlier a wrong is sought to be undone, less are the obstacles that one has to face; the further it is postponed, the more are the obstacles, and, therefore, the cost. If India decides to accumulate credit, it has to start with the ‘logic of good’, not the ‘logic of a concession’, which is merely changing the position of the obstacle. The ‘logic of good’ becomes operative on recognizing a principle as underpinning of the logic. In the case of Kashmir, that principle is the ‘right of self-determination’. When India accepts that as operative principle, credits would begin to flow to it.

All that has been said above, should underscore one basic point: The struggle in Kashmir must not stop short of Kashmir’s total liberation from India, that must remain the objective. The avenues that need to be explored and the measures and means that need to be adopted have to be numerous and must change with time and the prevailing situation. The intermediate objective, the strategies, and tactics in each field of endeavour – military or political, active or passive – must be subjected to constant debate, critical evaluation and review in order to ensure maximum efficiency. But as far the final objective is concerned, it should be one and must be strictly adhered to – without any rethinks, revisions or compromises. However, compromise is not a nonsense notion; it is an integral part of all social life – in the conduct of the state as well the evolution of a civilization. It governs all relations from the limited sphere of personal matters to the wider domain of statecraft. The example our Prophet (SAWS) in signing the Treaty of Hudaibiyah constitutes a precedence the Muslims can profit by following. Compromises were made in the ways and means for achieving the objective but not in the objective itself. But when compromises are made on the objective, which has often been the case with political elites of Muslims, they are rightly condemned as traitors and their action is regarded as ‘sell-out’. One has to bear in mind that a movement with ever-changing objectives is ultimately a movement without an objective, like a wandering person without a destination.

Another truth that needs to be understood is that the present condition of Kashmir (its being occupied by India and hence lost to Islam) is essentially a local manifestation of the global reality – the political powerlessness of Islam. It is this reality that is reflected elsewhere also by the fact of other important assets remaining lost to Islam. For example, Palestine and Al- Quds are also occupied – by the Zionists. The struggle for liberation in Kashmir that seeks to change the situation is geographically local but its impact would contribute to a change in the global reality. Liberating Kashmir from India’s occupation, in normal conditions, even if the movement is confined to Kashmir, would play a part in the evolutionary changes that affect the balance of power in the world, change perceptions and prospects. That is why it is so important to remain firm on the objective. Times change, so do prospects for success. Kashmir is influenced by the perceptions of it in the world particularly among Muslims in the World. Similarly, the situation in Kashmir influences the prospects of other legitimate struggles elsewhere in the world. As of now, the fifteen years of resistance – despite huge loss in life and property – has made gains more than losses. That the Kashmiri struggle is largely ignored by the world media and is demonised, portrayed as ‘terrorism’ and ‘proxy war’ of Pakistan, it has hurt India more than it shows. But that is not the point. The point is that time is now on the side of Kashmiris. If they remain firm in their objective, their struggle would bring them the ‘freedom’ they longed for so much.

At this point in time there is confusion – in Kashmir as well as Pakistan – about the objective of the struggle in Kashmir. It is not a land dispute. It is not a dispute between two brothers – one Hindu the other Muslim – who live on the same land. It is question of title and sovereign power. If the realities require the Kashmiri Muslims to compromise or abandon their claims, they need to change the realities first. Abandoning a rightful claim does not solve the problem; it whets the appetite of the one who imposed the unjust solutions in the first place. A compromise on the objective in Kashmir is to undermine the polity of Islam and dereliction of duty as Muslims. It must be understood that the balance of power or the nature of perceptions is fluid. Thus fluidity would serve those who are steadfast and persevere. Any faltering of resolve would prolong the war and increase losses. On the other hand, a success in Kashmir would register in the global power equation in favour of Islam. This is because the objectives, not the physical area of operation, determine the nature and extent of change. Ending the global powerlessness of Islam does not require Muslims to travel across the globe and locate the enemies of Islam and fight them. If the struggle in Kashmir is directed to objectives which cohere with the wider global objectives of Islam, success would change the reality of power, its perception, and the self confidence of Muslims every where. All this would happen even though the war is confined to a particular area and involves only a very small segment of the Ummah.

The vital point is the question of coherence that is most crucial. Objectives of the Kashmir movement must cohere with the wider global objectives of Islam. Except when sabotaged by organized secular-nationalist elites, all mass uprisings by Muslims have been in harmony and accord with the main objective of the time. In concrete terms, the wider global objectives of Islam in the present historical situation is the unity of Ummah that would result from a real change in the political-military balance of power in favour of Islam and against non-Islam. Muslims are now politically fragmented into nation-states, and globally the balance of power is decisively tilted against Islam and Muslims. This situation has got to be reversed. A total end to India’s occupation of Kashmir, and its union with Pakistan is an objective that is in consonance with the wider global objectives of Islam. It would strengthen the cardinal Islamic principle of Muslim solidarity. At the same time, it would defeat the jahilia notions and forces of nationalism by preventing Kashmir to emerge as yet another powerless and docile nation-state unable to play a substantive role in the world. Adding to the heap of already existing impotent ‘Muslim’ nation-states unable to decide or achieve a worthwhile purpose forever at the mercy of the powerful non-Muslims and foreigners. Therefore, the objectives and strategies of the freedom movement must cohere with the wider objectives of Islam. That must remain the guiding principle and overall objective of the freedom movement in Kashmir.

The Solution

The total liberation of Jammu & Kashmir from Indian occupation is the objective. The question is, how can it be achieved? After all the Indian army has not unintentionally strayed into territory of Kashmir that a random fire fights would scare them away. There is little likelihood that the Indian leadership would have such a change of heart that it concedes that the Kashmiris are not a part of the Indian nation and decide to pack up and leave. This is not going to happen because there is no internal or external pressure on India to do so. India sent its forces into Kashmir on the basis of a document (it calls the instrument of accession) that does not exist or had been forged for the day. Professor Alistair Lamb has written a book on the subject and his research revealed the truth about the forgery. India did all that and came into Kashmir with well thought through motives and far reaching ambitions. Depriving India of Kashmir will not lead to the break up of India but it would be a defeat of its hegemonic ambitions and imperialist designs. It is unrealistic to think that India will ever give up Kashmir voluntarily through negotiations or mediation. That is very unlikely. But that does not mean that Kashmir would forever be in India. It only means that India would have to be forced out of Kashmir, disgraced and humiliated, like all the aggressors throughout human history. How easily or how quickly would that happen is not the question; how certain is that outcome is the question.

In matters of honour and dignity, the peoples trampled underfoot for centuries have eventually asserted their will and triumphed against forces of coercion and repression. The verdict of history is that time is always on the side of those with high ideals or righteous objectives. A people struggling to redeem their honour and dignity always win; the degree of certainty is one hundred per cent. When an entire people pursue their objective single-mindedly, they achieve success more quickly. When they are prepared to make sacrifices to surmount difficulties they underline their sterling character and get honour and dignity before they secure their freedom. Normally one is prepared to face any amount of difficulty if one is reasonably certain about the result. The thought of difficulty does not become a deterrent for one who is struggling for a goal that is certain to be achieved. India’s defeat in Kashmir is a certainty. But for this to happen, the right ingredients have to be in place.

Every change has its own peculiar requirements, and once the right ingredients are there, constant human effort is there, it is only a matter of time – the time necessary for the completion of process – before the result appear, often precipitously. There are three essential ingredients for the ultimate achievement of success in Kashmir’s total liberation from India. Of these, the first two are absolutely essential, whereas the third one will facilitate the process. The ingredients are:

1) Movement inside Kashmir

A movement challenging India’s occupation of Kashmir must be maintained. At the end of the day, it is the ground situation inside Kashmir that has pivotal importance. If there were no resistance, there would be little prospect for liberation. The intensity of resistance would wax and wane but it must continue to exist and be as vocal as possible. The resistance to occupation can take many forms and entail several methodologies but it must have clear goals. In Jammu and Kashmir, the most vital objective of resistance is two-fold:

a) That Kashmir continues to remain ungovernable for India, and

b) The subversive forces stay intimidated and on the defensive.

The occupation by India has been facilitated by its success in recruiting political proxies to spy on and subvert resistance and to promote the agenda of the occupier. The collaborators among Muslims have undermined the resistance more than the India’s forces of occupation. Their activities need to be kept under close scrutiny and under check.

2) A Strong Pakistan

A Pakistan that has the courage, the will and the capability to stand up to India, if necessary, in a military conflict, is absolutely essential for the freedom of Kashmir. It is important to understand what that means because even in the high echelons of the Government of Pakistan the focus of Kashmir policy is not clear. Pakistan’s involvement in the present conflict in Kashmir is based on a very fragile foundation. It says that it supports the Kashmiri’s right of self-determination and their struggle to secure it. Thus, it presents its role in Kashmir to one of support, as one commitment among the many international commitments that Pakistan has around the world. Pakistan says it is a rightful cause and a noble cause. Pakistan says that it has a special interest in Kashmir that is recognised by the UN in the resolutions of the Security Council. But it does not say that the Kashmiris are essentially a part of Pakistan and that the struggle for the liberation of Kashmir is a Pakistani struggle and not merely of Kashmiris. This creates a lot of problems for Pakistan and it has to sustain so many unsustainable positions – for example, the position that Pakistan is only providing moral and diplomatic support to the Mujahideen in Kashmir. All that the enemies of Pakistan have to do is to prove that Pakistan is providing more than mere moral and diplomatic support and Pakistan is discredited as a liar. The stand adversely affects the authenticity and credibility of Pakistan’s case on Kashmir and robs it of prospects of securing active international involvement and diplomatic support. That is how it was so easy for India to discredit the liberation struggle as ‘terrorism’ and force Pakistan to end open support to the struggle that India called ‘cross border terrorism’.

The stand of Pakistan provides additional material to the sterile debate of unviable themes to the already stagnant political discourse in Pakistan. After unanimity over Kashmir for several decades, some regional and ethnic groups – including some from Kashmir – are seeking to sideline Pakistan in Kashmir. It has disastrous implication that go to the very heart of the polity of Pakistan and questions its national solidarity. Building the case this way seriously limits Pakistan’s options and the level of its involvement in Kashmir. India can use all its power to crush Kashmiris even though it is an occupying power but Pakistan cannot respond to the genocide of Muslims in Kashmir without risking an international war. It has not been properly understood that insurgency in Kashmir has removed many of the constraints and the options of Pakistan have multiplied. Pakistan can vary and stiffen its response to make the cost to India of its occupation higher all the time. Pretending to be only supportive is neither the truth nor good diplomacy. It is outright stupidity.

Pakistan has to build its Kashmir case on firmer historical foundations. It has to be honest, prepared to pay price for being so, and it will find steadfastness and honesty pays in the long run and that diplomatic success is impossible without both. Pakistan has to base its case for its involvement in Kashmir, on its legitimate claim on Kashmir, saying that India has illegally occupied what is potentially a constituent part of Pakistan. It is so on the basis of the very principle that gave birth to India and Pakistan in the first place, and the dispute of Kashmir is nothing but a historic fraud against Pakistan at the very stage of its formation. This fraud, though jointly committed by the then would-be Indian rulers (Indian National Congress led by Gandhi) and the colonial power, Britain, in 1947, has since been perpetuated, politically and militarily, by the state of India. It is ironic that apart from its de facto possession of Kashmir through armed aggression, India has no foundations for a credible case for its involvement in Kashmir. Yet India has built up a strong case saying Kashmir is its integral part ‘atoot ang’.

In contrast with Pakistan, India’s practical involvement in Kashmir is simply huge: there are hundreds of thousands (perhaps 700,000) Indian troops deployed in every corner of Kashmir killing and maiming Kashmiri Muslims, destroying their houses and dishonouring their women. In response to a few unoccupied hilltops being occupied by Pakistan in Kargil area, India launched a massive operation at high cost operation even though the hilltops were militarily insignificant and the operation was largely unsuccessful. Every Indian leader worth his or her salt made an appearance at Kargil and showered praise on the troops for ‘teaching Pakistan a lesson’. When Pakistan goes to world capitals telling them there is a freedom movement in Kashmir, India dismisses the whole case by a single phrase ‘Pakistan’s interference’ or ‘cross-border terrorism’. Pakistan pleads innocence saying it is only providing moral and diplomatic support. This way it becomes an extremely unequal contest: Pakistan has adopted a self-imposed weak position and given India a chance to occupy moral high ground that has no justification or foundation.

Pakistan should straightway question the very legitimacy of India’s presence in Kashmir. It was left to United Nations Security Council resolutions to decide who should vacate from Kashmir, India or Pakistan. The present movement in Kashmir has demonstrated beyond doubt that it is India’s military that commits war crimes and is unacceptable; India has to vacate. Pakistan should base its Kashmir case on strong foundations and let the whole world including India know very unambiguously that it is going to pursue its Kashmir agenda to its logical end and at all costs, including facing an all-out India-imposed war, which Pakistan should prepare to win. This message is very important: There are well meaning people who do not take Pakistan’s advocacy of Kashmir cause very seriously; they say that when it comes to the crunch Pakistan will buckle. The Indian leaders think that way and say so. With that kind of self-assurance that Pakistan would crumble in a crunch, they take nothing that Pakistan says seriously. They take it for granted that whatever happens in Kashmir, India would be able to hold on to Kashmir. It resorts to genocide in Kashmir because it serves two purposes – it intimidates Pakistan as well the Indian Muslims. They are certain that Pakistan can be dissuaded from hurting India too much by threatening invasion. Pakistan’s support has become the Achilles’ heal of the Kashmiri freedom movement.

To give such strong message to the world that Kashmir is a life and death issue for Pakistan, it has to construct its case on very strong foundation – Kashmir is in principle a part and parcel of Pakistan and its liberation is the first and foremost duty of Pakistan and its armed forces. Pakistan’s case is reinforced by India going back on its promise to hold a plebiscite in Jammu and Kashmir – a commitment it made to the world on the UN forum. It is betrayal to deny the plebiscite. The insurrection in Kashmir is the product of Indian betrayal. It could end as soon as India agrees to abide by its promise to allow a plebiscite to be held. Insurrection in Kashmir reinforces the claim of Pakistan. It is unparalleled and disgraceful incompetence that a people that can sustain an insurrection over 14 years cannot support it with suitable diplomacy.

Pakistan must claim that Kashmir is rightfully a constituent part of it. Pakistan – as a fact and the idea – emerged as a result of several Muslim communities coming together to form a large unit. Even at the point of conception, Kashmir was an included as a constituent unit (letter K in Pakistan) even when Pakistan was idea. There is no reason why Kashmir should have not gone into its constitution. That India refuses to hold a referendum or plebiscite shows that it knows what the people want – they want to be a part of Pakistan. When Pakistan relates to Kashmir this way, the talk of war will not sound unnatural. After all, war, per se, is not something unusual or strange to human civilization. Every sovereign country has a ministry of defence, maintains armed forces and has defence budgets. This is because every individual, society or civilization has some cherished values and interests which are vital to its survival, which it values more than life and is prepared to fight for it. Sovereign countries have armed forces maintained in readiness to fight, not to fight every day of the year but to dissuade anyone eager to or careless enough to hurt it. People that are not sovereign and have no army to defend them, can be hurt with impunity. Hurting a sovereign people is attended by cost. That is the point of being sovereign and maintaining armed forces in readiness to fight. India occupies Kashmir because it is prepared to pay the price of occupation.

Pakistan is unable to liberate Kashmir because it is not willing to pay the price that would attend its liberation. Those unwilling to pay the price for freedom do not save anything, they end up paying another kind of price that may not be lower in lives and money; but it certainly earns them dishonour. In fact, the crucial question always is whether a particular objective is worth a war, once it is regarded to be, war becomes legitimate. The defence of Lahore is worth a war with India, which I believe is the thinking in Pakistan. Why is it not worth fighting a war over? Considering that Pakistan has a meaning, and that the meaning came first then the word itself, what after all is the difference between Lahore and Kashmir? And, if there is, then Pakistan has no meaning, it is an empty 8-letter word, mere noise.

3) The Re-organization of India

India as it exists now, is the manifestation of the hegemonic vision that was developed in the later half of nineteenth century by the forces of resurgent Hinduism. In its original version, it encompassed the whole of the British Indian Empire. But Indian nationalism has no history whatsoever; it derives its inspiration from the British success in building a country by a combination of conquest and cunning. The agenda of India pursued by ‘nationalist parties’ such as the BJP and Congress, ever since 1947 includes, among other colonial projects in their neighbourhood, the dismantling of Pakistan. Since this involves a combination of subversion and invasion, as long as there is a country called India, a real threat of war – even a nuclear war – would continue to exist. Seeking the reorganization of India into multiple sovereign states based on genuine national identities (as opposed to an artificial ‘Indian’ identity) is an objective that is right in principle, as it is good for its many peoples. It is right because it is founded on the universal principle of ‘national selfdetermination’. This principle requires the people to define their identity as well as their destiny. India defines itself by a land mass and not by the objectives and aspirations of the people. India denies its people the right to decide their identity and their destiny. If India were reorganised as nation states like the rest of the world, its social and political fabric would be completely transformed and the objective of internal harmony as well as peace with its neighbours would be achieved without much effort.

All the states in South Asia are the product of the exercise of ‘national self-determination’ but India is an anachronism. It is an imperial state that is forever making trouble for its neighbours. However, it has not succeeded in suppressing the movements of self determination by diverting attention of the people outwards. On the contrary, it has underlined the imperial nature of the state structure by betraying peoples and resiling on promises and commitments it made to them from time to time. It betrayed the Sikhs, going back on the promise of a sovereign state and crushing their Movement of Khalistan even desecrating and destroying their holiest shrine, the Golden Temple of Amritsar in June 1984. It has betrayed tribal peoples of Assam particularly of Nagaland and oppressed Dalits systematically abolishing castes on the one hand and sharpening caste divisions and discrimination. The people of India, for their own sake, need to organise politically along ethnic and caste lines to crystallise their national identities and create a new structure of balance of power in which militarist agenda can get replaced by social and economic agenda[2].

It goes without saying that if India were reorganised on sans imperial lines, on the foundation of the principle of ‘national self-determination’ it would facilitate the liberation of Kashmir. Furthermore, this can also avoid the prospect of Kashmir’s liberation leading to an Indo-Pakistan war. One has to bear in mind that the Indian nationalist psyche is deeply haunted by the memories of Muslim rule over of India. They see Tughlaks and Mughals marching towards their territory even now, and since there are no such real marchers, they demolish mosques or kill Muslims or think of nuking Pakistan. Indian leaders repeatedly say they are facing threats, someone is going to take over their country, they never make it clear who is going to do that. Who after all is interested in a land where millions sleep on footpaths? But the world does not know that. What the ruling castes of India see nobody else can see with a normal eye – the Tughlaks and the Mughals. In all probability, therefore, when the Kashmiri struggle for freedom is close to success, India’s nationalist leaders may in their desperation, attack Pakistan. A reorganized India may save the world from that prospect.

If the above three ingredients are put in place in consequence of a focused, sustained, and strategic effort, the day is not far when Kashmir would be free from the rule of India. Having outlined the essential pre-requisites for Jammu and Kashmir to be free from Indian rule, it is necessary to strike a note of caution. The Kashmir freedom movement has come a long way. There have been sacrifices of enormous magnitude by the people of Kashmir. India and Pakistan are talking about lasting peace, and a tension-free sub continent. But peace does not come about merely by a wish; concrete steps are required to be taken for it to obtain and be lasting. The bus of peace may be missed again if the real aspirations and wishes of Kashmiri people are not properly ascertained or if they are not given due consideration. It cannot be overemphasised that the Kashmir issue, substantially, is a matter relating to ‘honour and dignity’ of a people. History bears witness that this matter far more in the lives of individuals and nations than matters of bread and butter. If the Kashmiri people are betrayed once again and their ‘will’ is not ascertained, or it is ignored or sabotaged, there would never be lasting peace. There might be some sort of peace, for some people and for some period of time, but it would not last. Lasting peace can only be achieved on the basis of a just solution, not at the cost of it.

When a people as a whole feel betrayed, cheated and let down, they will devise their own ways to rectify the wrong. They may be defeated, cheated or betrayed again and again but the process will go on. History teaches that matters relating to honour and dignity have an incredible potential to inspire the right men and women endlessly without any constraint of time or space. If Kashmiri people are wronged once again, a new breed of combatants (ordinary mortals who do not accept their despicable situation as a fait accompli but rise up to change it) will emerge, who will take up the mission with renewed zeal sometimes employing new and more effective methods. No one can stop this from happening: history does not accept managers and tight controls; it has its own dynamics and its own rules. On 13th July 1931 the Muslims of Kashmir rose in rebellion against Dogra rule. It was a spontaneous action that was ruthlessly put down. Many were martyred; many more were put in prison. The day is commemorated every year to honour those martyred on that day. Those fighting against India today are not necessarily linked by blood but they are linked by an injustice they struggle against. That link lives as long as that injustice thrives. As some die, some give up, but there are more new persons joining or forming new groups to challenge India’s occupation of Kashmir. This present phase started in 1989 but the movement never died once it started in 1947. Indian rulers arrested and killed the persons, but the process could never be arrested.

I was doing a Ph.D. in the beautiful Indian city of Pune. A young Kashmiri man, namely, Shiekh Tajammul-Islam, advocate by profession, raised the slogan of Kashmir’s freedom from India. It was a period of relative political lull following Indira-Shaikh accord in 1975. Tajammul’s call created a huge excitement, and so many young souls like myself rallied around him. Some young man, perhaps a teenager, somewhere, fired a single shot in 1989, and you have the whole population of Kashmir on the streets chanting the slogans of ‘azadi’ freedom from India. The point is, when it is a question of honour and dignity, truth and justice have an inherently huge potential to energise and galvanise human souls. It is this potential that creates movements, and those in power taking a narrow view of history, use brute force to crush the movement. If they succeed in that, the matter does not end. Control may be established for a time by wanton oppression or a deal, but the situation would erupt again later often with added ferocity. Those who are to participate in parleys and represent their peoples must remember that there is no compromise on matters of principle, honour or justice. Compromise can be made in timing and methods. It is the objective that makes a war noble or abominable.

[1] (On a personal note, I would like to place emphasis on a direct reference being made to the Kashmiri people to ascertain their wishes. Every adult Kashmiri man and woman needs to take part in making the choice and celebrate the end of tyranny and the arrival of freedom like their brothers and sisters in Sylhet and the Frontier Province of Pakistan.

[2] These points have been discussed fully in an article by Dr Syed Inyatullah Andrabi titled ‘India’s Nuclear Gamble: Underlying Motivations and Options for Future’ Institute of Kashmir Affairs Rawalpindi).

***

Dr. Syed M Inayatullah Andrabi is a well-known figure in the circles of political Islam. Born in Srinagar, the capital city of Indian Held Kashmir, Dr Andrabi has been intimately involved at the intellectual level with the global politics and political issues since his student days in 1980 at Pune (India), where he completed his Ph.D. in Linguistics in 1983 at the Centre of Advanced Study in Linguistics, Deccan College, University of Pune, Pune, India. Upon completing his doctorate he returned home to join the University of Kashmir, first on a post-doctoral fellowship and later as faculty, but could not continue because of the deteriorating security situation in Kashmir, and had to move to United Kingdom in 1994 where he continues to live since along with his wife and five children.