Anti-colonial feminist solidarity and politics of location

This piece is an attempt to think through the complexities and disjunctures in undertaking anti-colonial feminist solidarity work, confronting our complicities in the ongoing coloniality, violence and dispossession of marginalised peoples exacerbated by the state, in which we remain invested and from which we benefit. Here I am thinking specifically of India’s actions in the Kashmir valley and how we, as Indian feminist scholars, might engage in generative ways, not despite but because of our specific social locations. In a sense, this essay is also part of my ongoing engagement with critical scholarship on Kashmir, feminist theory, as well as feminist activist spaces in India.

While the disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir, especially the Kashmir Valley sees a protracted conflict and military occupation for decades now, it was in August this year that India’s parliament unliterally stripped the region of its nominal autonomy followed by a renewed military crackdown, including the arrest and detention of men and boys, political leaders, restriction on movement and communications blackout. Consequently, as many Indian photographers and activists embarked on ‘fact-finding’ missions in the ongoing crisis, Kashmiri writer Arif Ayaz Parrey in his sharp critique poses some urgent questions: what happens when Indian researchers, activists and artists obfuscate Kashmiri people’s political demand for self-determination but focus on their everyday ‘resilience’? What gets erased in only highlighting human rights violations while de-linking this occupational control from, and as a result of people’s desire for freedom? Further unpacking the colonial underpinnings of such a gaze that seeks to address human rights and valorise resilience, Parrey argues that not only does it inflict epistemic harm but also perpetuates material violence on people by presenting cases of human rights violations or stories of everyday survival as untethered from the wider militarised state machinery and its quashing of political resistance. It is thus, ‘[b]y putting us on a pedestal, these people want to deify our flesh-and-blood struggle into an unattainable myth’ (Parrey, 2019). In a similar vein, Mir (2019) insists that Indian photographers and artists critically think through their own caste, class and citizenship privileges including state patronage which grants them access to Kashmiri narratives as well as platforms to publish their work, in which Kashmiri people’s political demands are often left out to push a politically reductive ‘humanising the conflict’ narrative.

Indeed, disrupting this coloniality of knowledge production on Kashmir remains a key undertaking of emerging critical Kashmir scholarship. This is also because for a long time, scholarship on Kashmir was largely written from security studies and international relations perspectives, and bounded within nation-based, nation-state and bilateral (India and Pakistan) theoretical frameworks, often eliding Kashmiri people’s conceptualisations of the conflict. Relatedly, Kumar and Dar (2015) in their study of Indian historical writings on Kashmir valley argue that the scholarly impetus to view the Partition of India as the starting point of the contemporary political conflict omits indigenous struggles against the Dogra monarchy since 1840s and again, onwards 1930, and the demands for self-determination which predate the Partition. For them, this epistemic misrepresentation is a result of over-reliance on state archives and narratives that has led to the marginality of the politics of Kashmir, which is largely seen through the lenses of Indian nationalism. It is in this sense that Kashmir’s history and the political roots of the conflict remain subaltern to Indian history and epistemological accounts, which largely operate through the binary framework of anti-colonial and nationalist struggles (ibid.; 42). Knowledge production on Kashmir thus becomes a principal site of contestation where Indian nationalist politics, and its coloniality are shaped and perpetuated but also resisted, with as much vigour, as can be seen in the emerging critical and transnational feminist scholarship.

—

Being a student of feminist and gender theory where scholars and activists have long foregrounded the need for strong reflexivity and carefully thinking through one’s own social positions of caste, class, location, citizenship and their seepage into the research process, I was shocked but not surprised with the total silence of many Indian scholars on addressing their own complicities, dis/comforts, accountability as well as consequences of their research and writing on Kashmir. This is especially in view of India’s ongoing coloniality or what Huma Dar calls the ‘Brahmanical occupation’ of Kashmir. Importantly, Dar’s conceptualisation underlines that Brahmanical supremacy is manifest in Kashmir’s occupation, in which all Indians, particularly upper caste Hindus remain differentially invested or complicit. It is worth mentioning that academic institutions the world over remain dominated by upper caste academics. It is in this context that I then read the blanket silence as an epistemic sleight of hand where in not calling out occupation, Kashmir was indeed construed as ‘integral’ to India without saying so in as many words. Along with significant political impacts, theoretical repercussions of this unwillingness to engage with difficult and uncomfortable questions about one’s own position or the mechanics of occupation included marginality of gender as an analytic and feminist epistemology as a research orientation within early scholarship on Kashmir, as suggested above.

In thinking of critical politics of location here, I am not endorsing an autobiographical disclosure of one’s locations, which often stops at that or donning a form of academic innocence (I am thinking of and intellectually indebted to Da Costa’s critique of academically transmitted caste-innocence). Rather, I learn from Rich and Borsa’s push towards reflecting ‘on the spaces and places we inherit and occupy, which frame our lives in very specific and concrete ways’. Indeed, they shape our ways of seeing the world, our theoretical and political commitments, our conceptual investments including what research questions we ask, to whom, in what ways and what gets erased and left out in this process. Sumi Madhok[i] (2019) further insists on reflecting on our theoretical frameworks, whether they need to be arranged differently, our citational practices that acknowledge the ‘knowability’ and ‘thinkability’ engendered by scholars often occupying the margins of the academy as part of our commitment to a critical politics of location. In the Kashmir context, this could entail thinking beyond the victim/agent binary in relation to gendered politics and resistance; thinking through the mechanics of military occupation, its masculinist underpinnings; and how cultures of militarism in India, their nexus with securitisation – for example, viewing Kashmir as a ‘security problem’ – demonises the Kashmiri people, especially Muslims as ‘misled anti-nationals’ while perpetuating militarised violence against them. Most importantly, such a conceptual reoritentation would centre people’s epistemologies, experiences and knowledge of the conflict. Relatedly, Osuri reflects on her position as an Indian scholar and what it means to build anti-colonial, feminist solidarity with the people of Kashmir: ‘…it is precisely a desire for accountable knowledge that can challenge our scholarly assumptions and generate an affective solidarity. This form of solidarity can also serve as a critical method for the nexus between scholarship and politics.’

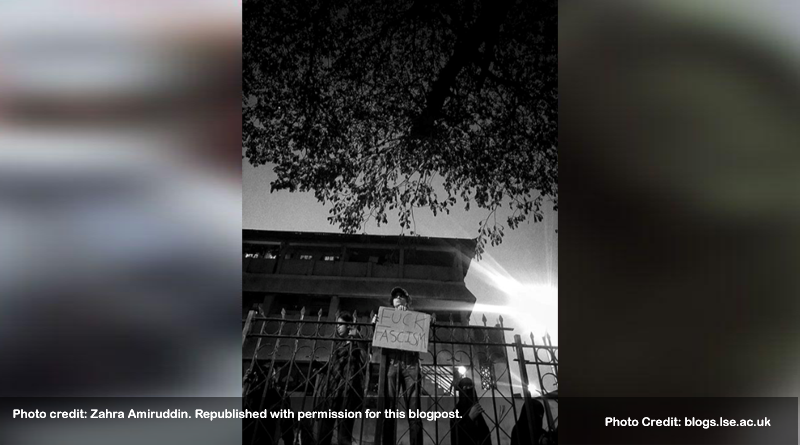

Indeed, acknowledging one’s silence, complicity and role as Indian citizens in maintaining occupation as well as systemic marginalisation of Kashmiri people was nearly absent during my engagements with mainstream urban feminist activist spaces in the cities of Delhi and Bombay too. I am reminded particularly of a protest that I took part in Delhi following the rape and killing of a young girl belonging to a Muslim tribal community in Kathua of militarised Jammu and Kashmir in 2018. Organised by a liberal civil society coalition, the framing of this protest elided conditions of militarised control, ongoing communalisation of the conflict in the region while constructing this rape as another case of violence against women in India. Here, solidarity was yet again placed in a citizenship and nationalist framework while erasing historical and material realities of occupied communities. Kazi (2007) has long cautioned against subsuming militarised sexual abuse under the umbrella of violence against women in India without taking note of the social particularities, enforced militarisation in Jammu and Kashmir as well as militarism in India that perpetuate violence in Kashmir. Likewise, a few Indian feminist virtual groups that I continue to be part of have not adequately engaged with the anti-feminist siege in Kashmir or its effects on the people. Instead, there have been sorry letters by well-meaning Indians to Kashmir. Yet again, without calling out occupation and people’s right to self-determination, one ends up centring oneself – the Indian citizen, their guilt and apologies on behalf of the oppressor state ad infinitum. Instead, we may consider asking: where does this guilt take us? Are we demanding that the state be held accountable and take responsibility for inflicting systematic violence? Or does this guilt bind us in a lock; it disenables us from thinking of solidarities we can forge, state accountability that we can demand from our respective positions without centring ourselves and our narratives? And how, then, might sections of mainstream Indian feminist and liberal movements be complicit in erasing or underplaying the occupation in Kashmir?

—

I read Parrey’s essay in conjunction with Shaista Patel’s (2019) deeply important critique of ‘Complicity Talk…’ where she notes how upper-caste South Asian scholars situated in Western universities are quick to extend solidarities to marginalised people ‘elsewhere’ but disconcertingly ‘at the expense of attending to other occupations that are in our backyards’. Patel’s argument is not a simplistic one; she does not ask us to merely ‘look at our backyards’ but is mindful of how the act of witnessing is never innocent or de-political but an exercise of privilege. Patel’s contention is that we constantly question our own complicities, make ‘a commitment to politics based on self-critique grounded in ongoing reflections and asking hard questions of ourselves’ (2019). Some such questions could be: how is our silence or failure to demand accountability from the Indian state complicit in the intense militarised control of Kashmir? What caste, class, citizenship privileges shape this silence? What are our complicities and who benefits when we do not call out the occupation of Kashmir as control without popular sovereignty?

Where does this leave us then? As feminists have long suggested, the work of solidarity must be continually re-thought and re-examined, and remains an ongoing political investment, an ethical responsibility with no definitive answers but situated responses, strategic retreat as we listen to and unswervingly centre marginalised people, their voices, experiences and their demands. I learn from Ather Zia who in a recent webinar raised rightful concerns about nation-based, liberal Indian feminist movements reifying victim/agent binary or aiming to ‘protect Kashmiri women from ‘demonic Islamic’ patriarchy’ without thinking through unequal gender relations and how they are exacerbated by militarisation and occupation. Importantly, Zia, in many ways, foregrounds anti-colonial, anti-occupation, anti-capitalist, anti-caste, anti-racist and anti-patriarchal values as constituting feminist politics.[ii] Indeed, a feminist worldview, a political investment that needs repeating ad infinitum.

My thanks to Priya Raghavan for a generous reading of this essay.

Niharika Pandit is a PhD researcher at the Department of Gender Studies, LSE. Her research examines gender, militarisation and narratives of home.

[i] Dr Madhok shared this in her intervention in LSE Department of Gender Studies event on ‘Politics of Struggle: Current Issues in Feminist Knowledge Production’.