Some Strategic Thoughts on the Achievement of Islamic Objectives in South Asia

(This paper was written in August, 97, where the idea of ‘South Asia Institute’ was developed. It was written as a follow-up to a meeting of few like-minded people in Leeds.)

A: RECAPTULATION OF THE MAIN POINTS AGREED UPON IN THE 30TH MARCH (1997) MEETING

- Islamic doctrine being creative of a social order and, therefore, of a civilisation and polity, attaches great importance to the defence of its physical assets, regarding them as absolutely indispensable.

- Peoples, material resources, lands and territories, heritage are the physical assets of Islam.

- Kashmir being a Muslim land is an important physical asset of Islam, that our noble ancestors brought to its fold, but the same being under Hindu subjugation now, remains lost to Islam.

- Reclaiming more and more physical assets for Islam, which necessarily includes the reclamation of the lost assets, is a common duty for every Muslim man and woman, regardless of his/her colour, race or place of birth.

- Liberation of Kashmir from India has to be envisaged in the framework of a series of changes, which though by itself important, will also make the liberation of Kashmir practically realisable.

- The changes have to be engineered in:

Kashmir——leading to its total liberation from India

India———-leading to its political reorganisation

Pakistan——leading to an Islamic order there - Cumulatively, the changes must lead to the mobilisation and consolidation of Muslim political power in the South Asian region, home to almost 48% of whole Ummah.

- A think-tank organisation needs to be set up here in Britain with the main purpose of engineering the changes mentioned at (vi).

- Dr Syed M I Andrabi should come up with some suggestions and recommendations of strategic nature regarding how the envisaged changes can be brought about.

B: STRATEGIC THOUGHT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

1) Understanding the Nature of Various Changes

The changes envisaged are:

Liberation of Kashmir (Hitherto C1)

Political Reorganisation of India (Hitherto C2)

Islamic Order in Pakistan (Hitherto C3)

Now let us try to understand the nature of C1-C3. This will help us to locate them individually in their respective historical environments, and also enable us to appreciate how at the same time they do and do not form a single package.

C1——This change is about ending direct control of Kufr over a Muslim people. Historically speaking, Kashmir is still in a type of Colonial era i.e. under direct control of Kufr. What C1 in real terms means, is:

Colonial era à neo-colonial/ Islamic

Kashmir will move from Colonial era to either neo-colonial i.e. Secular-nationalist Order or directly to Islamic Order. The former is so far the dominant pattern of Ummah’s recent political history. Muslim peoples one after another got ‘independence’ from Colonial rule, but only as far as direct control is concerned; Indirectly the forces of Kufr remained dominant. Now suppose, if under the present political leadership of the Movement in Kashmir, with Pakistani ruling elites in the supportive position, Kashmir is liberated from India, C1 will mean: Colonial àneo-colonial Era. If instead, C1 is engineered by Islamic Movement, a change direct from Colonial to Islamic order will happen, although historically that has not been the pattern so far for the rest of Ummah.

C2——-It is closely related to C1. Historically speaking, the changes envisaged in C2 in effect mean the so-called de-colonisation, if India is considered an empire, which it really is, and not a post-colonial nation-state. C2 means end of the post-British Hindu Empire and the emergence of so many nation-states which should have actually happened in 1947. For example, the turn that the Sikh political history had to take in 1947—moving from a British Colony to a sovereign nation-state—-it has to take now.

C3——-It is rather different from, both, C1and C2. C3 basically means a change from the Neo-colonial Order to the Islamic one. As such, it is a part of the wider change i.e. C3-type change in the rest of the Ummah. From this perspective one can legitimately raise the question about C3’s position in the wider domain of C3-type change. For example, is not a C3-type change more urgent in Hijaz or Egypt than in Pakistan? The answer to that lies in C3’s being a part of the package, which means that C3 is not only directly important to us; it is indirectly as well, and in the present scheme, its indirect importance overrides its direct one.

One can understand now that the set of historical forces one has to confront in the process of C1 and C2 are different from those to be taken on in the process of C3. While in the former it is mainly the ‘Pan-Indian’ Hindu hegemonic forces, in the latter it is the post-colonial ruling elites, institutions and systems that are sought to be defeated. It may happen, as is often the case, that our enemies in C3 could be( or rather happen to be) our allies in C1. The secular-nationalist elites(our enemies in C3) form a part of anti-colonial struggles regarding them as nationalist causes. This is happening in Kashmir now; this happened in the Indian sub-continent earlier(Pakistan was delivered to Muslims by these elites), and same thing happened in Algeria in the 60s. At this point, one may rush to the conclusion that C3 should not be linked with C1 and C2 because of their different natures. However, there are reasons behind C3’s inclusion in the present package. The reasons are (a) historical, and (b) strategic.

Historical—Pakistan in the first place emerged as a symbol of defiance against the emergent post-British Hindu dominated order in South Asia. In C1 and C2, when we are talking of defeating the Hindu hegemonic Forces, we have to consider Pakistan, as a matter of historical fact, to be the leading edge of the movement against these forces. The leading edge is blunt and does not have the strike capability, but that is precisely what should be one of the main dimensions of the change sought through C3: the sharpening of the leading edge.

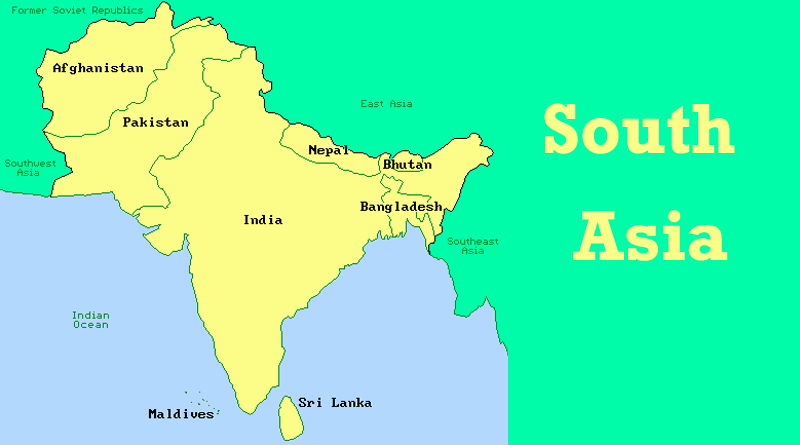

Strategic—In C1 and C2, both, It is the state of India that is the negative target of change. As such, India’s strategic environment becomes crucially important This environment is India’s neighbourhood, Pakistan and Bangladesh being most important in that, and to a lesser degree Nepal as well. However, when it comes to the understanding of issues such as strategic environment, India’s neighbourhood, Pakistan’s strategic importance in that, and the like, we have got to take a closer look at India’s current thinking and the strategic realities of the Region.

2) Some Strategic Realities of the Region

With the political reorganisation of Indian sub-continent in 1947, a configuration developed where India’s strategic outlook became Pakistan-centric and that of Pakistan became India-centric. In this strategic equation both were destined to be losers: Pakistan, because India being in a decisively stronger position, it could never equal India, let alone dominate it; and India, being locked-up in a power rivalry with a small neighbour, was undermining its own big power status and prospects for a wider global role. Things are, however, changing now. India’s outlook no longer remains Pak-centric. In the recent years there have been some significant measures by India of entering into strategic relationships outside its immediate neighbourhood. Relations with Iran, and the recent grouping of the Indian Ocean Rim countries, bringing together India with South Africa one the one hand and Indonesia one the other, should be seen in this context. By doing this India is, in a way, not only strengthening its strategic position, but also redefining its strategic identity: from a merely sub-region-confined power, stronger than just its smaller neighbours, to a global actor, interacting and strategically engaging with other powers in a bilateral, regional and global context. Apart from mutuality of interests(which keep on changing), India has been trying to build-up political relationships on the comparatively durable basis of common cultural/civilisational bonds. In this regard, India’s political thinking is guided by long term considerations, and political think-tanks in India seem to be influenced by Samuel Huntington’s thesis of the clash of civilisations. They link India’s ‘Go East’ policy—forging ties with the countries to its East — to this long term political scenario i.e. civilisational clash. It has to be noted that almost all the countries to the east of India have a strong Indic/Hindu element in their culture. From Indonesia to India it is almost a single civilisational core. Islam has made the difference(in case of Muslim countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh etc. etc.) but some commonness in the civilisational substratum persists. In case of the Non-Muslim East, however, the civilisational affinities with India are naturally very strong. If we talk in terms of Dr Shariati’s classification of religions into Abrahamic and Non-Abrahamic, most of the India’s east is Non-Abrahamic, whereas, the west, starting with Pakistan, is almost wholly Abrahamic. On the basis of this cultural commonness, India has been building political relationships with Thailand, Burma and other countries in the Region. Thai foreign minister, recently in India, announced the formation of an economic grouping comprising India, Thailand and Bangladesh in the first instance, with Burma and others to be included latter. India is also taking a keen interest and active role in the Region’s international system, for example, in (A)ssociation of (S)outh (E)ast (A)sian (N)ations and ASEAN ®egional (F)orum. This policy of ‘going East, is one of the dimensions, along which India is redefining its political and strategic environment.

Now let us come to the strategic environment of Pakistan. As mentioned earlier, Pakistan also remains a loser as long as it remains bogged down in the 1947-determined strategic environment. Pakistan needs to reorient its strategic outlook—give it a westward push ,or to be precise, north-westward. The South Asian regional political order, as was established by the British and subsequently maintained by global powers US and ex Soviet Union, envisaged India as the main South Asian Power with Pakistan as a small India-subservient country in the region. This places Pakistan in an extremely vulnerable strategic position. Pakistan can relocate itself strategically, by converting its religious/cultural/historical/geographical neighbourhood(the countries to its west and north-west) into a strategic alliance. At the moment this is not the case. Pakistan’s religious/geographical allies are not its strategic allies.US assistant secretary of State for South Asia, Mrs Robin Raphael in a routine testimony before the House Foreign Relations Committee in the US Congress noted with satisfaction a couple of years ago, that Iran and Pakistan being neighbours geographically are, however, rivals strategically: They are following conflicting strategic objectives in Afghanistan, Mrs Raphael said. But, we must note, if things change and Pakistan succeeds in relocating itself, it will not only improve its strategic position substantially, it will change its strategic identity as well: From a small India-subservient south Asian state to the Gateway of Central Asia—the most important emerging region of future power rivalries. With this strategic position Pakistan will have much more effective and meaningful role in the South Asian sphere as well. I am not aware, weather this thinking has formed a part of strategic thought in Pakistan. Unfortunately, the neo-colonial states like Pakistan, who are known to have inherited everything(from systems of governance to life styles) from their colonial masters, seem to have inherited, from them, strategic outlook as well. However, there are some facts that have been seen by political analysts as being reflective of this strategic thinking in Pakistan. For example, when the late PM ZA Bhutoo convened an Islamic Summit in Lahore and took measures for closer relations with West Asian states(Central Asian states where then a part of Soviet Empire), it was construed as a West-ward reorientation attempt. Likewise the expansion of (E)conomic (C)ooperation (O)rganisation,(which earlier comprised Turkey, Iran and Pakistan) into a sizeable regional block, admitting into its fold Afghanistan and other newly independent Central Asian Republics is also seen as Pakistan’s Westward thrust. However, given the docile nature of the state of Pakistan, one can not read much into these moves—particularly the strategic considerations(if any) behind them—- and also, one need not. What we need to note is that, there is a consensus in the strategic community that an alignment with its west gives Pakistan a tremendous strategic depth against India. In this alignment, Afghanistan is the first necessary link. Now one can understand the strategic significance of a very clear historical fact: the Durrand line, separating Pakistan from Afghanistan has been hostile to the former right from its inception in 1947.This effectively blocked the way for Pakistan’s westward orientation, and confined Pakistan to its sub-continental environment facing a far bigger hostile India as the regional Chief, and always involved in futile bickering with it on its own. This scenario fitted perfectly well into the British established political order for south Asia. As a result of Afghan Jehad the situation was bound to change; Pakistan being an active supporter and physical base of Jehad. The historical Pak-Afghan hostility was bound to end. But soon after the Soviet defeat and the Mujahideen take-over of Kabul, India got itself firmly entrenched there and worked through, both, open and discreet channels to ensure that a Pakistan-hostile regime rules Kabul. India’s aid to Rabbani government in Kabul is no secret: Rabbani during the Food Conference in Rome last year openly thanked the then Indian premier HD Deve Gowda for his financial and other types of support. This was only to deny Pakistan the opportunity, that had come its way for the first time since 1947, to make a strategic link-up with its west. India’s extreme discomfort at the Pakistan-friendly Taliban take over of Kabul has to be seen in this context. I have thoroughly gone through all the press material pertaining to India’s perception of the post-Taliban Afghan situation, its reactions and concerns. India’s main concern is the strategic depth that Taliban take-over gives to Pakistan against India. India has also been fearing escalation in armed activity in Kashmir as a result of possible Taliban influence or direct involvement there, but that again, is the function of the main consequence of Taliban take-over—providing strategic depth to India’s rival, Pakistan. The above discussion throws some light on the strategic realities of the region involved in C1-C3. That in turn highlights some strategically important dimensions of these changes. For example, C3 must, as a necessary part of it, seek to bring about the strategic integration of Pakistan with its west, particularly Afghanistan. Whereas it will have a stabilising effect on Pakistan, by the same token, it will have adverse effects on India’s strategic and security environments, which in turn will facilitate C1 and C2.

3) C1-C3: Criteria for Fixing the Right Priorities

C1-C3 need to be ordered in some kind of an order according to their respective priorities. Although, when it comes to practically pursuing such closely related Islamic targets as C1-C3, there hardly remains a watertight dividing line between what has to be done and what not. But nonetheless, priorities should be fixed and then stuck to, if for nothing but to ensure the optimum utilisation of human and financial resources, which always happen to be very limited and, therefore, precious. However, priorities can be fixed only on the basis of empirical criteria. These can be identified along two dimensions:(i) Current,and(ii) Historical.

On the current dimension the decisive considerations, that constitute the criteria can be: (i) The ground situation as it exists now (ii) Strategic importance of a particular (C) hange in the overall scheme (iii) Chances of success (iv) Need of effort i.e. whether a particular area is already being attended to, or neglected.

On the historical dimension Historical Precedence is the criterion. I have learnt this principle of historical precedence from the late Dr Kalim Siddiqui, and, therefore, I will refer to it, henceforth, as Kalim’s Principle. The principle goes like this: When we want to bring about a political change, we have to look at the whole historical process through which all those political realities emerged that we want to change now. What was prior(in time) in that process, should be prior in the future process of change as well. Dr Kalim stated this principle in the context of political change in West Asia. He argued that historically Arab nation-states were created first, then only at the end of the process the illegitimate entity Israel was planted with Arab nation-states functioning as a protective fence for the unholy entity. To undo this, Kalim argued, the protective wall has to be dismantled first, then only proxy state Israel can be done away with.

4) A Case for C2’s Priority

On the basis of Current as well as Historical criteria I will plead for C2’s priority..

Starting with the current criteria let us take up the social and political situation in India as it exists on the ground now. The relevant things to be noted in this connection are:

- There are a number of active as well as dormant independence movements in India. Among the latter Sikh Movement is most important and among the former the movements in north-eastern region of India(starting from Assam and extending to Nagaland, Mizoram, Tripura) are very important. The North-East of India, since it borders Bangladesh, Burma, Bhutan and China has always been considered strategically very important. Accordingly the Indian rulers take very seriously, the so-called insurgency in this region. The present Indian Prime Minster IK Gujral, just within one month of his assuming office visited the Region for about 5 to 7 days and so did his predecessor Deve Gowda. Both offered unconditional talks to the armed Guerillas, which they rejected. One has to briefly note following points about this region and the movements there, so as to get an idea of why Indian rulers take the situation in this region so seriously.

*Linguistically, culturally, religiously and socially the Region(particularly Nagaland, Tripura, Mizoram) does not share anything with the rest of India. Religiously the inhabitants of this region are either pagans or Christians (a lot of Christian Missionaries operate in the Region) with a sizeable Muslim population in Assam(about 45%). Society is tribal. Except in Assam, the languages spoken are non-Indo-Aryan.

*Assam is the main source of India’s off-shore oil, timber and world-famous tea.

*The Guerrilla groups in this region(particularly Nagaland and Tripura) are very well entrenched. They are well-armed, well-trained, highly organised, motivated and resourceful. Indian Defence Minster recently disclosed that these groups are getting arms from Khymer Rouge of Cambodia. The leaders of these groups, mostly Marxists, are ideologically well-trained and some of the veterans are reported to have met such top figures as Mao-tse-tung in the past. One can safely compare these groups with their Marxist counterparts in South and Central Americas. - Regional parties (representing local aspirations, problems and issues) are becoming more and more popular, and for the first time since 1947 India is ruled by a coalition of regional parties, even at the central level. This reflects a deeper reality to which we will turn next.

- The deep-rooted and age-old conflicts in the Indian society, caste-conflict on top of them, have started surfacing. Of all the facts on ground(for example those mentioned in (i) above) this is the most important and politically significant one. This shows that the process of India’s social and political fragmentation has started, and that the process is irreversible. The truth is that Indian society has been the most conflict-ridden societies from the ancient times. One can’t talk in terms of ‘high’ and ‘low’ castes only; there are sub-castes within every caste, ‘low’ and ‘high’ castes within the ‘low’ caste, and so on and so forth. In the recent past its political leaders managed to suppress the conflict, but for the past some years it has been surfacing with devastating political consequences. The most visible consequence is that political issues and agenda are becoming more and more localised and no common issue which could be called ‘Pan-Indian’ is effectively binding the people. This I am reporting on the basis of my knowledge of the current Indian situation. What is so important about the surfacing of caste-divide, is that it is a real divide, vertically very deep and horizontally wide—so wide that, as I learn from the press reports, it is becoming a crucial factor in India’s forthcoming Presidential elections even. How significant and meaningful these developments are, one can appreciate only when viewed in a historical perspective, as will be done at (5) below.

Coming to another Current criterion, namely strategic importance, it seems that the reorganisation of India into smaller political units i.e.C2 holds the key for the realisation of Islamic objectives in South Asia, or for that matter the wider region including Central Asia. It is often said that the change in the environment of India i.e. strengthening of Pakistan and liberation of Kashmir from India and its union with Pakistan will lead to ‘disintegration’ of India. True, Kashmir’s liberation may send strong liberationist impulses throughout India and C1 may have a snow balling effect. This view is widely shared by most of the anti-India forces in Pakistan, Kashmir and elsewhere and they really believe in it. I am not sure how far Indian think-tanks really believe in such a view, but the politicians there talk of it very frequently and when explaining to the world outside why Kashmir is so important for India, they express exactly the same fear—India breaking up in the event of Kashmir’s liberation. Generally it sells well; the world community ‘appreciates’ India’s fears and by implication its toughness on Kashmir. So it works to India’s advantage. I believe this break-up of India viewpoint is a sensible one, but at the same time I do not take it to be the only possible scenario that can emerge as a result of environmental changes (C1andC3) around India. An alternate scenario (here, on this point I seek your special attention) is equally plausible: liberation of Kashmir and/or Pakistan turning Islamic and becoming more stable and strong can lead to consolidation of India. How?

Whatever the divides— their natures and numbers, both, fact and theory inform us, that all the Non-Muslim (for that matter Non-Christian, Non-Jewish, Non-Parsi) population of India can and gets emotionally united under the blanket label of ‘Hindu’, when it comes to fight for a perceived ‘Hindu Cause’. Coming to the theory in a moment, let us note some very prominent factual instances: all the ‘Hindus’ (of every caste and denomination) were successfully mobilised by the dominant elites at the time of Babri Mosque demolition. Before this, when Bharitya Janata Party(BJP) Leader LK Advani set on a Rath-Yatra (A Hindu long march undertaken for an invasion)—the main event in the run-up to the final act of demolition— he drew huge crowds everywhere en-route, and in the General elections that followed soon after this Long March, BJP’s number of seats in the Lok Sabha(Lower House of Indian Parliament) went up from a humble double figure to 110(If I remember correctly, from mere 11). Since anything against Pakistan is perceived as a ‘Hindu Cause’, Pak-bashing continues to be a vote-fetcher in India’s electoral politics. The most prominent instance of this is Mrs Indira Gandhi’s (the late PM of India) unprecedented landslide victory in 1971, soon after the break-up of Pakistan, in which she played a prominent part and the people in general perceived it as such.

Now turning to the theory, the basic truth to know is that the term ‘Hindu’ does not refer to the adherents of a definite religious order. It was in the first place used by the Muslim conquerors of Turkic/Persian/central Asian origins to refer to inhabitants of ‘Al-Hind’. They called the people living in ‘Al-Hind’ as Hindu. In a way this amounted to conferring a common identity, albeit geographical, on a people who were hitherto known by their caste, tribal, occupational and linguistic identities. Professor Romilla Thapar of Jawahar Lal Nehru University, New Delhi , has written an in-depth research paper, drawing from ancient Sanskrit textual evidences to the modern ones, on this topic. In post-Muslim India this geographical identity ‘Hindu’ was gradually converted into a religious identity—a negative one, referring to all those who do not follow an extra-territorial(outside the territory of India) creed like Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Zoroastrianism etc.etc. ‘Hindu’ thus became a socio-religious identity used as a blanket term for all the various adherents of the indigenous ancient Indian religious/cultural/civilisational tradition, which is basically a pagan tradition of tremendous diversity deriving from India’s (mainly North India’s) ‘history’, which being no different from mythology(as is the case in Greek paganism), ultimately boils down to geography i.e. rivers, mountains, valleys etc. etc. Present day Hindu fascist forces in India take care to make a distinction between indigenous and outside non -Hindu creeds. For example, Buddhism (indigenous) although regarded a non-Hindu creed is yet not equated with Christianity or Islam(outside). It is interesting to note that the term ‘Hindu’ is negatively defined in Indian Constitution as well: anyone who is not a Muslim, a Jew, Parsi, Christian, Buddhist, is a Hindu. It was for this reason that Sikhs after the emergence of independence movement in Punjab made a bonfire of this particular article of Indian Constitution demanding its repeal. So, facts apart, in theory also ‘Hindu’ is a blanket term. All the Indian castes and tribes who follow one or the other territorial creed are lumped together as Hindus.

What emerges from the above discussion is that the very term ‘Hindu’ as a socio-religious identity is negatively definable. As such ‘Hindu unity’ is also negatively achievable and sustainable i.e. with a visible enemy as the focus of unity ( an enemy-perception enhances unity, it does not create it, as is the case here). A careful study of Indian freedom movement shows that at the very early stages of its development, two important intellectual tasks were accomplished: the notion of a Pan-Indian (spanning the whole area of British Indian Empire) monolithic Hindu community was formulated, and Muslims projected as the negative focus of this unity. This was done by recourse to a particular construction of history that depicted a ‘golden Hindu age’ having been disrupted by Muslims. So when Pakistan came into being, it was seen by Hindus as symbolising that old disruptive evil force, which had, in the past, taken on the forms of Mughal, Tughlak and other Muslim empires and which had destroyed the mythical glory and unity of the ‘Hindu community’. Thus Pakistan became and continues to be the negative focus of ‘Hindu Community’ and by implication that of the political concept and entity ‘India’ whose bedrock was and continues to be this notion of a single Hindu community. Now it is for any body to guess that given a hypothetical situation of there being no Pakistan, could the notion ‘Hindu Community’ or the entity ‘India’ have survived at all. The more stronger and Islamic Pakistan becomes, sharper becomes the focus of Hindu unity, and if Muslim Kashmir asserts its distinct identity and comes out of India, the focus can become even more sharper. This is the logic on the basis of which an alternate scenario of India’s consolidation as opposed to its disintegration can reasonably be visualised.

The alternate scenario visualised above, does not imply that Pakistan should have not come into being, or that it should not become Islamic and strong(C3), or that Kashmir should not be liberated(C1). What it implies instead, is that C1 and C3 should not be pursued while ignoring C2. For example, the process of the liberation of Kashmir should keep pace with the process of India’s social fragmentation, the splitting of mythical Hindu Community and the level of empowerment and organisation of India’s 200 m Muslims.

Staying with the Current Criteria, when we come to the criterion ‘need of effort’, C2 clearly deserves a priority. Not many serious minded Muslims realise the crucial importance of C2, let alone do something in this regard. Particularly at intellectual level, the field is almost barren.

Coming to the Historical Criterion let us apply Kalim’s Principle to the South Asian situation. I am aware that these two situations—South and West Asian– are not wholly comparable; for that matter no two situations are, but nevertheless we will try to see if Kalim’s Principle helps us to better understand the historical process in which those political realities, that we want to change through C1-C3, came into being. After all, at the basic level it is the same story: historical advance of Western Civilisation.

The first thing that seems to have happened after the British arrival in the sub-continent is the empowerment of Hindus: all the subsequent developments are a result, reaction or a consequence of it. The huge India that emerged in 1947 is a direct result of it; Pakistan a reaction, and Kashmir a consequence of Hindu hegemonic ambitions. Hindus after failing to stop the emergence of Pakistan, remained determined to deny it stability, legitimacy and viability as an independent political entity. Occupation of Kashmir was a reflection of this determination. When the historian of Western Civilisation will trace its course of historical growth and development in south Asian region, he will record, as the first major political development, the empowermwnt of Hindus—the political rise of a hitherto unknown species the ‘neo-Hindus’(as some historians call the early western educated Brahmins). Hindu ideologue the late Girilal Jain, also the former editor-in-chief of The Times Of India, is very explicit on this. He believes that a fundamental shift took place in the power balance between Hindus and Muslims as a result of the consolidation of British Raj. This is also a well known historical fact that the British could only consolidate and expand at the expense of the entrenched Muslim power, whom they had displaced, which automatically meant the empowerment of the other section of population, i.e.Hindus.

By saying that they were a reaction to the emerging Hindu power, I do not intend to underrate the importance and worth of Pakistan or that of other Muslim efforts and achievements. What I mean to say rather is that, Muslims after the British arrival in India, did not on their own, understand and analyse the new situation properly and envision their political destiny. They did plan, they made efforts and strove a lot, but only when the new reality of British-Hindu nexus and Hindus leaving Muslims far behind and going to become the future rulers of India, started unfolding before their eyes. What our great well-wishers like Syed Ahmad Khan, Allama Iqbal and Jinnah(one may differ with their prescriptions but better not doubt their pro-Muslim intentions) did was to try to salvage the Muslim interest in an extremely hostile situation. Caught up in a situation, their main concern remained: what little can be saved now(typical of a fire-fighting exercise). Allamah Iqbal hailed for his Pakistan ‘ideal’, while speaking at the Muslim league session of 1930, backgrounded his Pakistan Proposal by highlighting the difficult situation that was created for Islam and Muslims. He said: “Never in our history has Islam had to stand a greater trial than the one which confronts it today”. His proposal was, therefore, not an ideal in the real sense of the term, it was a possible way out in a very difficult situation.

What emerges from the above discussion is the truth that Hindu empowerment has historically preceded all other unpleasant realities that we want to change now. Demolition of Hindu power should constitute a priority then. That is what C2 is all about.

5) Looking From the Historical Perspective: More on India’s Ground Situation

The facts on the ground mentioned above, encouraging though they are, do not however suggest that an overnight change is going to take place in India. Such changes as the one of political reorganisation do not come about that instantaneously, but what is important is, that the process in the right direction has started. By right direction I mean that the whole process through which the present India has come into being, is sought to be reversed. Things are happening in that direction. India is the end product of a long drawn process, that converted a conflict ridden society with small group identities into a modern Indian nation and a nation-state India on its basis. Gandhi’s movement and his role in coining a ‘pan Indian’ identity and founding a nation, for which he is rightly called the Father of Nation, is the most prominent and commonly known part of this process. However, we need to have a fuller view of this process in order to appreciate better, how it is being reversed now.

Soon after the arrival of British in India, the Brahmins(‘high’ caste Hindus) were the first to embrace Western culture and education and this resulted in their upward social and economic mobility. With Muslims lagging behind, these Brahmins or neo-Hindus began to harbour political ambitions and a lust for political power. However, the British had laid down the ground rules and the neo-Hindus had to conform. Their first necessity to get the power became the creation of some sort of a single Hindu community, not in reality (which was none of their concerns) but in theory, and this was the first step in the process mentioned above(the process through which India came into being). As professor Romilla Thapar notes:

“The need for postulating a Hindu community became a requirement for political mobilisation in the nineteenth century when representation by a religious community became a key to power and where such representation gave access to economic resources…Since it was easy to recognise other communities on the basis of religion, such as Muslims and Christians, an effort was made to consolidate a parallel Hindu community. This involved a change from earlier segmented identities to one which encompassed caste and region and identified itself by religion which had to be refashioned so as to provide the ideology which would bind the group”

The political ambition dictated that there be a well-knit large single community, but the social reality was otherwise: a conflict ridden society with segmental identities. In these circumstances the neo-Hindus set out to ‘reform’ Hinduism. From early 19th century onwards, a whole lot of neo-Hindus came to be zealously engaged in the task of ‘reform’, and all these efforts together constituted, what in the official Indian version , is known as Hindu Reformist Movement. There is an awful lot of literature on this movement and apparently this is taken to be the moral-intellectual basis, of the political freedom movement launched later in the 20th century. The Reform Movement is supposed to represent the whole package of lofty principles, great values and high precepts and beliefs underlying India’s freedom movement. The truth is, however, totally different: All these ‘reformist’ attempts constituting the so-called Reform Movement were basically a considered response of neo-Hindus to the conflict situation, and were aimed at neutralising conflicts by providing, what Professor Thapar says above, an ‘ideology which would bind the group’. All those high-sounding phrases, such as Hindu Tolerance, Non-violence, Secularism, etc. etc. disguised as beliefs and principles in the literature of Reform Movement, were merely tactical tools to neutralise and contain the conflict, and thereby create, in theory, a monolithic huge Hindu/Indian community. Professor Ainslie T Embree(professor of History at Columbia University and General Editor of the Encyclopaedia of Asian History) has dealt with this matter in detail and he believes that the so-called Hindu Tolerance, Secularism etc.etc. were the tools that the neo-Hindus employed to deal with the conflict. For example, Secularism, which in the West meant negation of religion, was given a different meaning by neo-Hindus, namely that all religions are equal. By employing the tool of Secularism, neo-Hindus like Gandhi sought to neutralise the religious conflict. But as Professor Embree points out, all these were temporary measures; not only that they could not make any real difference to India’s social reality, where conflicts were age old and deep rooted, they actually sowed the seeds of further conflict. Now as the ground situation in India tells us, all the neo-Hindu tools stand exposed, having outlived their effectiveness. All the tools and methods that were employed in the process, which converted a crowd into a nation, have been clearly discerned by the fast emerging social forces in India and they look determined to undo the whole impact of these tools and methods i.e. reversing the process. Take for instance, the tactical tool Gandhi used for neutralising the caste conflict. In order to absorb the ‘low caste untouchable’ Hindus(preventing them from going their own independent way) Gandhi called them ‘Harijans’, which means ‘sons of God’. This was regarded as a very honorific title by the ‘untouchables’ and they rallied behind Gandhi—the trick really worked. Now one of the main political parties of ‘untouchables’ BSP(presently the ruling party in Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest province with a population of over 250 m, and a sizeable Muslim population) challenges the whole Gandhi legacy, publicly swearing to destroy it. Its chief, Mr Kanshi Ram, when asked why his party is against Gandhi when it is he, who gave them such an honorific title of ‘sons of God’, Mr Ram gave a very sharp reply. He said: by calling us ‘sons of God’ he glorified a situation that, in real terms, was extremely ignoble and shameful, and by doing this he wanted to legitimise and perpetuate that ugly situation. In this reply one can see to what extent the neo-Hindu tools stand exposed, and this way the process, that the neo-Hindus had initiated, is effectively getting reversed. The original reality has started surfacing. The neo-Hindu-imposed artificial ‘pan-Indian’ identity is fast giving way to original real identities like Sikhs, Dalits, etc. etc. As mentioned earlier, the issue of identity is coming to the forefront of Indian politics, and the social groups are asserting their distinct political existence with a sense of vengeance. Again as an instance one may cite Ms Mayawati’s statement (She is an ‘untouchable’ and Chief Minster of Uttar Pradesh), she made when asked why she and her party BSP want to destroy Gandhism, when it is Gandhi who did so much for the nation. Mayawati replied : but what he did for us? This reply of Mayawati, typifies the psychology of assertion of the deprived social communities, their strong sense of communal identity and of deprivation.

6) Islamic Response to the Indian Situation

Islam will look at the Indian situation from two angles:

- Islam seeks, as one of its main strategic objectives, the complete unity and consolidation of Momineen i.e. the Believers, and disintegration of Kufar. This two-pronged strategy ensures the dominance of Islam over the Kufr, thereby ensuring peace and security for the humanity at large. The unity of Kufar has no genuine foundations and accordingly no ethical value, and leads to ‘fasad’ i.e. tumult and mischief on the earth. The forces of Kufr lying in a state of disarray, provides the proper security environment for Islam. Therefore, Islamic response to the current Indian situation will be to promote the centrifugal trends there.

- Islam provides a wider and higher platform for the unity of all mankind. The diverse cultures and general ways of life(if they do not contradict Islamic teachings) of different peoples and communities while remaining in tact, Islam provides a platform that, being Divine, is equidistant to all i.e. community A finds it as much her own, as does the community B, and so on and so forth. Naturally there is no coercion, no imperialism of any sort. Kufr on the other hand, does not provide a universal platform; it is a particular tribe/nation that, in the name of unity, aims at imposing on others its way of life, culture and ‘values’, which means imperialism. Islam does not allow it. While calling to unity and insisting on Islam being the only genuine platform for that, it upholds the rights and liberties of individual nations with respect to each other, and does not allow the weak to be swallowed by the big. As such, Islam will uphold the movements of national self-assertion in India like those of Sikhs, Nagas, Dalits etc. etc. particularly when they are oppressed.

In the light of above, what we should do now is first to take a due cognisance of the emerging situation in India, and then chalk out the best strategic course of action. What seems to be important and relevant now, is to provide intellectual foundations to this current social shake-up in India. That will provide it proper roots and will ensure its survival. We also have to keep in mind that there can be, nay there are, so many extraneous factors also involved in this process, as a result of which, this social stir may not reach its natural political consequences. For example, US, and for that matter whole of the West—its political leadership as well as academia, does not see India as a monolithic entity the way Indian leadership would like it to see. The West has always been appreciative of India’s cultural diversity and the existence of so many distinct cultural communities. Bill Clinton just some three years before, openly spoke in favour of ‘Sikh rights’. But West’s leadership is solidly behind India’s political integrity and there so many reasons for it.(I have discussed these reasons in detail in my last paper ‘Kashmir Conflict’). So if left to these extraneous factors India’s social stir may not lead to its political reorganisation. Also, as is generally the rule, the dominant and entrenched power-elites(who are mainly Brahmins) sensing the inevitability of change, may jump on the bandwagon only to determine the direction of change, and naturally its results. In the Indian context particularly, one has to be more careful about it. There is a long tradition of powerful anti-establishment movements having been sabotaged and ultimately absorbed in India. Sikhism is a prominent example.

So, although the facts on the ground are very significant, yet their natural outcome can not be taken for granted. A deliberate, and independent input by Islamic Mov’t with its own long-term calculations is definitely needed. The present ‘rights’ movements can mature into liberation movements. We should set up an academic centre in London and go about producing excellent research reports about the objective situation in India. We have to talk in terms of real identities, like Muslims, Sikhs, Dalits, Bengalis etc.etc., and on the basis of objective research, facts and figures, have to build up reasonable and credible cases of the deprivation of these communities’ political, religious/cultural, economic and social rights. The discourse built up over a period of time, will subsequently make our articulation of agenda regarding India—its total political reorganisation—-a natural, publicly legitimate and acceptable effort. Also our discourse, revolving around the historical as well as contemporary Indian reality, will sharpen the sense of deprivation among those who already feel deprived, and will create this sense among those who do not feel it now.

Above all, the academic centre will build up a genuine and authentic political discourse regarding the recent political history of South Asia—a discourse that fits into the overall paradigm of Islamic movement. Such a discourse is hitherto non-existent, unfortunately. A neo-Hindu-designed Master narrative largely dominates the Muslim understanding and analysis of recent sub-continental history and the contemporary Indo-Pak affairs. As an example, just consider two ‘standard’ formulations, and check the content of truth in them.

One ‘standard’ formulation is that India was partitioned in 1947, and as a result, Pakistan was born. This is the basic premise: depending upon one’s viewpoint someone endorses it, saying partition was the right thing; and someone regrets it. But every one shares the basic premise that an event of India’s partition really took place. Now look how untrue the above formulation is and how much it is rooted in the neo-Hindu worldview. It is untrue because nothing was partitioned in 1947. The geographical area known as India was politically organised as an empire up to 1947. On the demise of British empire the whole domain had either to be returned to Muslims from whom the British had got it, as Hong Kong was returned to China, or it was to be politically reorganised on some other basis. Since no independent Muslim power(like China in case of Hong Kong) having a rightful historical claim to the lost domain ‘India’ did exist, the area under the empire had to be politically reorganised on an alternate basis. This is what really happened: the area under the British empire was reorganised into national sovereign units—India and Pakistan in 1947, Burma and Sri Lanka(which were parts of the Empire) in 1948. Burma was in fact the province of British India, yet, does anyone characterise Burma’s emergence as a separate independent state(like Pakistan) as partition of India? That there really existed a monolithic Hindu community coextensive with the frontiers of Empire and on the basis of that an ancient country ‘India’, is a neo-Hindu fiction that they fabricated for their own political and economic reasons. The truth is, there was no country as such that was partitioned; India was the name of a geographical area—a subcontinent, like Australia, which, however, is a continent. Countries came into being later i.e. after 1947, after the so-called act of partition, emerging from this geographical area. Also, please note, how the Hindu intellectual origins of the concept of ‘Ancient Country’ become clear on a slight reflection. The neo-Hindu worldview that underlies the Master narrative, does not only presume the existence of an ancient country, but also that this country belonged to Hindus. If it was not so, then why the emergence of Pakistan alone, and not that of India as well, amounts to partition? If an ancient country not exclusively belonging to Hindus did exist and was partitioned in 1947, the emergent parts of it(Republics of India and Pakistan) have equally to lament and blame the other for partitioning his country.

Now look at the dreadful implications of this neo-Hindu narrative. In Pakistan if a train is late by five minutes, people start talking about the inefficiency of the railway system, then of the government, and lo! In a moment the discussion boils down to: was the creation of Pakistan in 1947 a right step? Questioning the existence of the country—this most unfortunate situation is unique to Pakistan. People question the government, the policies, or at the most the whole political system, but never the very existence of their homeland. But this happens in Pakistan because according to the neo-Hindu narrative(accepted as the standard version of events), India with its temples and Shiv Lingams(lingam means the male sexual organ, and Shiv Lingam refers to the sexual organ of Shiv, name given to a Hindu deity. Shiv lingams are holy for a section of Hindus and they worship it.) was there on the crest of earth from day one, Pakistan emerged just in 1947, that also by ceding from the ‘Mother India’.

Another ‘standard’ formulation , in the neo-Hindu narrative is that the British ruled India by divide and rule policy. If it means that the British promoted the already existing divisions, exploited them for their own ends and sowed the seeds of further division, that is perfectly acceptable, because this is what every colonial ruler does to perpetuate his rule. However, in the ‘standard’ narrative ‘divide and rule’ means something else: British divided a united Indian population. Because of this meaning Pakistan’s emergence is also treated as a result of the British divide and rule policy. Most of the Muslims, particularly the anti-West ‘revolutionaries’ subscribe to this meaning of divide and rule. Hardly they care to think, that by subscribing to this view, they are taking a very important historical fact for granted, namely, that the Hindus and Muslims in India were a united lot before the British arrival. Now, this is nothing short of a blunder. One cannot and must not take facts, historical or otherwise, for granted. A proper research establishes the authenticity or otherwise of such facts. My limited inquiry reveals that there was no such thing as Hindu(non-Muslim)-Muslim unity—social, cultural—ever existing before the British came. On the basis of her research into early inscriptions, Professor Romilla Thapar reports, that foreigners in India were called ‘Malecha’, meaning impure. This term goes back to Vedic Texts(i.e. at least 2000 years back) and refers to the non-Sanskrit speaking peoples outside the caste hierarchy, or to those regarded as foreigners. A 14th century inscription from Delhi refers to Shahabud-din, a Muslim King, as ‘Malecha’. This is a commonly known fact, that in India overseas travel was regarded a taboo, because of the notion of impurity associated with anything outside the territory. People from outside or native people having professed an ‘outside’ faith e.g. Muslims were regarded impure. This is also because there is no concept of conversion in Indian Hindu thought and one’s birth into a particular caste defines one’s religious identity. Hindus always thought of native Muslims as foreigners or ‘sons’ of foreigners. Even today, Muslims in India are nicknamed as ‘Babar ki Aulad’(sons of Babar). One can imagine that in a society, where Muslims were considered impure, what kind of unity(reportedly destroyed by the British) would have been possible. It is from this premise, namely, the British divided and ruled, that the neo-Hindu narrative wants us to believe that there was a complete unity—unity under Hindu leadership i.e. Gandhi, and whatever was outside it(the Muslim movement, for example) was because of the British machinations—- they divided the ‘united’ people.

7) Kashmir: Case for a Movement

As far as C1—the liberation of Kashmir from India is concerned, there seems to be a credible case to suggest that it can better be brought about by a kind of movement rather than an academic institution. Two reasons against the desirability of academic institution are, briefly, as under:

- The Kashmir problem, in its general sense, has already passed the stage of intellectual debate and argument. Regarding the wider and deeper issues involved in the Conflict, they form a part of the subject matter of research to be undertaken in the proposed academic centre relating to C2. Academic institutions represent a pre-political phase of a movement aimed at bringing about a particular change. This pre-political phase involves proper and rigorous conceptualisation, production of ideas and making them marketable in the wider intellectual and political community, projection of ‘vital’ issues and introduction of ‘new’ themes on the basis of research, so that, over a period of time, these themes and issues occupy the centre-stage of political discourse. For example, the ‘issue’ of fundamentalism was picked up by politicians, after it was ‘created’ by the strategic intellectuals. This is very clear that C2 calls for an academic institution but in case of C1 things seem to be rather decided. Kashmir is not an integral part of India, the territory is disputed, people want freedom from India—all these are well established and universally accepted positions. Why then go back to pre-political phase?

- Apart from paving the way for a well-informed movement, academic institutions also serve an important political purpose of lending respectability, credibility and legitimacy to the on-going political/military movements pursuing the same cause with which the academic institution is concerned. Thus, for example, an academic institution concerning itself with the reorganisation of India, apart from its long term targets, will effectively encourage the on-going movements in Punjab and North-East and will lend them and their cause a wider credibility. However, in case of Kashmir, the fact is that the Kashmir Cause is a universally accepted one and enjoys the credibility of a genuine political problem, which hardly needs to be enhanced by the patronage of an academic institution.

8) C1: Two Main Objectives

Two main objectives that have to be pursued with regard to C1, are:

- An effective and a sustainable resistance, at all levels, against India has to be ensured inside Kashmir.

- The timely sentiment, generated by the present movement of Kashmir, must be converted into a permanent commitment.

Muslims world wide have been mobilised to varying degrees by the present movement in Kashmir. However, this mobilisation is the creation of the present movement, and is, therefore, unlikely to survive it. Given the fact that by all available indications, the present movement may not lead to Kashmir’s total liberation from India, one can safely conclude that the present mobilisation cannot be relied upon when it comes to pursuing the objective of Kashmir’s total liberation. However, this mobilisation is the greatest asset having ever been available to the Kashmir Cause. The only problem with it is the fear, that it may prove temporary. But then, a temporary sentiment can be successfully converted into a permanent commitment. This is a standard practice in political engineering, but it requires a lot of skill. The most familiar way of doing it is through institutionalisation: seize on the present capital i.e. awareness, sentiment, concern, enthusiasm , and provide it a channel for consolidation and further growth through an institution. In this case, something like Kashmir council(a name picked up for the sake of convenience) can be set up.

9) Kashmir Council

Kashmir Council (KC) will try to bring together overseas Kashmiri and other Muslim individuals, groups and organisations on common minimum program, the bottom line of which will be rejection of India’s occupation of Kashmir and maintaining a struggle against it up to the time the occupation is completely vacated. The council will be a forum of consultation, will mobilise support for its program and will act as a public spokesman on Kashmir. The council will pursue a demand based agenda and will put the demands directly on national and international governments/political systems/organisations/institutions. For example, instead of asking Britain to tell India to do so and so, it will put a demand on the British political system itself. As an instance, KC, on the basis of Kashmir’s internationally recognised disputed status and the genocidal conditions obtaining there, can make a very reasonable demand that Kashmir be taken off the White List of countries that includes, among others, India and Pakistan. This is not very important from the point of view of asylum-seeking , but has definitely a tremendous political significance in highlighting the Kashmir Cause. The whole idea behind direct demands method is to sharpen the otherwise vague agenda of the presently on going overseas Kashmir activity. For example, in the recent British elections, Kashmiri population (from Azad Kashmir), sought ‘pledges’ from their respective candidates that they will ‘raise’, ‘talk or speak about’ the Kashmir Issue. Now, what does all that mean in practical terms? In fact, some go to the extent of seeking the ‘pledge’ from MPs that they will definitely ‘solve’ the Kashmir issue, as if it is Britain who has to solve it. As we know, they do not mean to do anything in the first place, but with these vague demands put to them, these British politicians manage to get off easily without getting exposed. KC will make precise demands and will employ activist approach like campaigning, sit-ins, rallies etc. etc to pursue the demands. KC will be established after a due process, but to be a credible institution it has to take some necessary measures. The most necessary measure KC has to take, is to secure full confidence of the genuine and revolutionary part of the movement in Kashmir, and a general acceptance from the wider anti-India circles there. This may require effort but is definitely possible.

10) Strategic Questions Before Kashmir Council

Also, KC has to resolve some important strategic questions regarding the Kashmir movement. Chief among them is the question that which operational framework for the struggle of Kashmir’s liberation KC favours? State Vs state or Movement Vs state framework? I will explain what is meant by this:

Kashmir has so far been a contentious issue between two states, India and Pakistan, who have apparently fought three wars over it. However, what India has been doing from the beginning, even from1930s i.e. prior to its occupation of Kashmir in 1947, was to project Kashmir as an independent and main party with itself as a ‘supporter’ staying firmly behind. This was a clever strategy of keeping things in real control, yet giving out the impression that it is Kashmir that is deciding for itself its political course. India could do this only after successfully infiltrating the political field of Kashmir in early 1930s.Cutting a long story short, what we see now from 1989 onwards is, that with the inception of the present movement in Kashmir, Pakistan has almost duplicated India’s strategy. While maintaining real control, it has pushed Kashmiris to the forefront, giving out the impression that Kashmiris have stood up against India with Pakistan standing firmly behind. In real terms things have not changed much: Kashmir conflict continues to be an Indo-Pak conflict with the freedom movement in Kashmir virtually becoming a source of strength for Pakistan. This has its own advantages. The most apparent one is that Pakistan is involved with India on behalf of Kashmir, and being a state and, therefore, stronger than the movement, Pakistan can sort out things with India better than the movement can. But that exactly is the weakness also. Pakistan cannot afford to raise its level of conflict with India on Kashmir beyond what is permitted by the general framework of Indo-Pak relations at a given time and in a particular regional and international context. Pakistan is always advised by ‘friends’ and foes alike not to create tension in the region and settle the matters amicably. On the other hand Kashmir’s liberation from India involves raising the level of conflict with that country to the highest. Based on this logic, there is an alternate viewpoint that the struggle for the liberation of Kashmir should be carried out in the operational framework of Movement Vs state. It should be movement of Kashmir Vs the state of India, with Pakistan as an active supporter. On one side it should be the movement of Kashmir with Pakistan and possibly others like Afghanistan, Chechenya as supporters, and on the other, the state of India. In this framework the situation becomes very much like that of Northern Ireland, where it is the Republican movement with Irish Republic on the one hand and British Government on the other. Although a state is more powerful than a movement, yet the later has its own unique advantages. It enjoys liberties which a state cannot. The way Sin Fein went back on its(i.e. IRA’s) cease fire promise, a state could have not. Movement Vs state option becomes particularly preferable in cases where long -drawn and sustained struggle is needed.

KC has to decide between the two operational frameworks explained above. May be, at a deeper reflection, it may turn out not to be a case of either/or choice, but, nevertheless, I believe there is an element of choice involved. I am also aware that movement Vs state viewpoint(the one I explained above or something like this) has been advocated by some nationalists in Kashmir. However, I have independently arrived at this. It is, after all, the thought-process through which a conclusion is reached at, and not the conclusion itself, that makes the real difference. One more factor, that can help KC to decide between the two options, is that movement Vs state option seems to fit better in our general scheme of political change in South Asia. After all, we would like a host of movements emerging all across India and exerting pressure on the state. Kashmir movement seen as an independent entity confronting Indian state, can accelerate that process, whereas a Kashmir movement seen as an instrument of Pakistan and, therefore, a case of Pak meddling in Indian affairs, can have exactly an opposite effect: it can impede or, at least, cannot accelerate the on going process of social fragmentation in India; Pakistan being the negative focus of India’s unity as described earlier.

Another strategic question that the KC has to resolve is: does it represent the cause of freedom of both Kashmirs i.e. Occupied Kashmir(Kashmir occupied by India) as well as Azad Kashmir(the part of Kashmir with Pakistan), or only of Occupied Kashmir.

Generally, Kashmir problem is presented this way: in 1947 the Indian sub-continent was politically divided into India and Pakistan and the Princely states(the small quasi-independent states) existing then, had to decide to accede to either of the two—India or Pakistan. Unfortunately the state of Jammu and Kashmir, that included Occupied as well as Azad Kashmir then, being one of the princely states, was not allowed to exercise the free choice of acceding to either Pakistan or India. Therefore, it is said, political future of J&K state is yet to be determined, and this is what UN resolutions of 1948-9 are all about. Those advocating Kashmir’s total independence, however, reject the idea of limited choice between India and Pakistan.

KC cannot subscribe to the above formulation, as it goes against its worldview as well as strategic thought.

Against the worldview—- because the above formulation places the Occupied and Azad Kashmir on a par with each other. Saying that their political future is yet to be decided, it implies that both of them face a same political problem, which is not true. Occupied Kashmir faces the problem of Hindu occupation, Azad Kashmir faces no such problem. People of Occupied Kashmir, before anything else, have to rid themselves of the alien occupation; those of Azad Kashmir being a part of Muslim polity have to struggle along with other Muslim brethren of Pakistan to establish an Islamic Order there.

Against the strategic thought—— because in the above formulation it is often said that 1947 agenda is yet to be finished. That is, Kashmir has to become a part of Pakistan, so that the division of sub-continent into two-nations—Muslims and Hindus—becomes complete. UN resolutions also effectively say the same thing, based as they are on the Independence Act of 1947. Our strategic thought makes us look at the things rather differently. We do not see a bi-national Indian sub-continent before or after 1947. It was and is a multi-national one. On one side Muslims, according to their faith as well as secular criteria, form a single brotherhood or ‘nation’; on the other side there are numerous nations one excelling the other in their respective genuine claims to nationhood. The notion of a single Hindu nation, on a par with Muslim ‘nation’ according to the Two-Nation Theory, is a myth and is thoroughly politically motivated as discussed earlier. Our whole program in C2 is based on complete rejection of this myth. Therefore, when we talk of the whole pre-47 J&K state as disputed and invoke 1947 scheme for its solution saying that a solution according to that will take the scheme to its logical end, we are certainly lending legitimacy to that scheme, which we should not. The principle of Muslim unity is an eternal one, and need not be ‘approved’ or ‘justified’ by Two nation Theory. Kashmir once liberated from the alien occupation can become a part of the larger Muslim polity, Pakistan, even without there being any Two Nation-Theory around. No theoretical or historical justifications needed for what is clearly a principle of Islam and also its vital political interest.

Apart from ideological and strategic considerations, one more problem that arises by taking the ‘freedom’ of Azad Kashmir on board , is that the KC cannot act as some sort of a ‘government in exile’, which it could otherwise(satisfying, of course, other required conditions), because there already exists a government in Azad Kashmir. So at the end, it seems that KC has to basically represent the cause of Occupied Kashmir’s freedom. However, it has to be weighed against an important practical consideration: there is a ‘powerful’ Kashmir movement in Britain and it is mostly the movement of Azad Kashmiris. They constitute an important financial resource, that cannot be just ignored. Also whatever amount of support we can get from British political system, it is only through them. They constitute strategic minorities in so many constituencies and political parties take a due notice of it.

C: ORGANISATIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS

The task that we have set for ourselves needs an organisation, both, here in Britain as well as on the ground i.e. in the geographical areas where changes are sought to be engineered.

1) Organisation in Britain.

There will be a two tier organisation, consisting of an upper tier and a lower tier.

Upper tier will consist of an apex body, a supreme majlis-shura. The Shura will:

- function as a think-tank, fix priorities and targets,

- function discreetly and not have a public posture,

- be the ultimate decision making body and in-charge of policy planning,

- make final decisions about funds collection and allocation,

- supervise and co-ordinate the functioning of subordinate institutions,

- be responsible and accountable for advancing the set task with all the sincerity and honesty, and for identifying and mobilising human and financial resources.

Lower tier will consist of institutions with a public face. At the beginning two main institutions are proposed:

(i) SOUTH ASIA INSTITUTE (SAI)

- SAI will be an academic centre based in London, with mainly research and publication activities. It will promote vital themes and issues through conferences, seminars and regular bulletins.

- SAI will have a pivotal role in C2, and that is precisely its foundational purpose.

- SAI will be headed by a full-time director who will be assisted by, at least, one full-time research assistant. Latter’s job will involve very frequent travel to India.

(ii) STANDING COMMITTEE ON KASHMIR

This will be a non-academic institution constituted by some responsible Muslim individuals, preferably those involved in Jehad movements. A Taliban representation in the Committee will be highly useful. The Committee will work towards the achievement of two objectives related to C1, mentioned earlier. These two objectives, to repeat, are (a) maintaining an effective resistance in Kashmir, and (b)establishment of Kashmir Council.

2) Organisation on Ground

The places where organisation has to be built up are Pakistan, India, Kashmir, Bangladesh and Nepal.

It is suggested that we should build up a two-sphere organisation in the above-mentioned places. There should be an inner sphere or the core group of fully committed individuals, and a periphery, comprising people of influence from media, bureaucracy, industry, academia etc. etc. The periphery can be identified on the basis of a bottom line which will vary from place to place. For example, in case of India the bottom line can be a commitment to political, economic and cultural decentralisation. Periphery can keep on changing, whereas the core group will be permanent.

D) RECOMMENDED MEASURES

i. After the present writ-up is properly discussed, the Majlis-Shura should be set up, and the practical measures towards the establishment of the proposed institutions i.e. SAI and Standing Committee on Kashmir should be initiated forthwith.

ii A Fund (for example by the name of Kashmir Fund) should be set up to finance the whole activity

***

Dr. Syed M Inayatullah Andrabi is a well-known figure in the circles of political Islam. Born in Srinagar, the capital city of Indian Held Kashmir, Dr Andrabi has been intimately involved at the intellectual level with the global politics and political issues since his student days in 1980 at Pune (India), where he completed his Ph.D. in Linguistics in 1983 at the Centre of Advanced Study in Linguistics, Deccan College, University of Pune, Pune, India. Upon completing his doctorate he returned home to join the University of Kashmir, first on a post-doctoral fellowship and later as faculty, but could not continue because of the deteriorating security situation in Kashmir, and had to move to United Kingdom in 1994 where he continues to live since along with his wife and five children.